BREWSTER AND CROTON FALLS BOTTLES- WATER RIGHTS- JOHN FRANZ HISTORY

![]() WATER RIGHTS- JOHN FRANZ AND THE CREATION OF THE NEW YORK CITY WATERSHED IN PUTNAM COUNTY.

WATER RIGHTS- JOHN FRANZ AND THE CREATION OF THE NEW YORK CITY WATERSHED IN PUTNAM COUNTY.

When John Franz started his bottling works in Croton Falls in 1872, he had no idea thirty years later he’d see his beloved village just one more time after being forced from his home and business. John came to Croton Falls a tiny village 50 miles north of New York City in 1866. Six years later he opened a small bottling works on the west side of the Croton River in Somers, N.Y. (Oddly people who lived in that part of Somers had allegiance to Croton Falls and used the Croton Falls mailing address. So even though John’s business was in Somers newspaper accounts for the time record John as living and working in Croton Falls.) To avoid confusion this article will refer to John as living in Croton Falls. Franz’s business grew but not without controversy. During the 1870s John battled the Croton Falls Temperance League run by G. W. Abrams of the village. With the influence of Abrams and the League, Franz and several other men were arrested. Franz was charged with providing free liquor at his establishment. The prosecution could not prove its case and the charges were “withdrawn.” According to the Brewster Standard, a jury found the other men not guilty of their charges leaving all respected citizens surprised and indignant and the “peripatetic” beer to flow unbound. With G. W. Abrams silenced Franz’s outmaneuvered one obstacle but the biggest threat wouldn’t come from within Croton Falls but from a very thirsty monster 50 miles away.

WE NEED WATER

The 19th century saw New York City grow into the biggest metropolis on the North American Continent and with this growth came a need for more and more water. According to the NYC Environmental Protection website, the first settlers in the City drew their water from wells located in the City. Eventually, a reservoir was constructed and a large well sunk. “As the population of the City increased, the well water became polluted and the supply insufficient. After exploring alternatives for increasing supply, the City decided to impound water from the Croton River, in what is now Westchester County, and to build an aqueduct to carry water from the Old Croton Reservoir to the City.” After years of construction, the Croton Aqueduct was placed into service in 1842. The aqueduct was able to supply the City with 90 million gallons of water per day, however, from day one there was always an understanding that the City would eventually need more water and according to the Brewster Standard “in 1857 -58 the Croton Aqueduct Department made a careful… survey of the Croton watershed… with a view to locating all possible sites for dams and… reservoirs.” Eventually “new reservoirs were constructed to increase supply, Boyd’s Corner in 1873 and Middle Branch in 1878. In 1883 a commission was formed to build a second aqueduct from the Croton watershed as well as additional storage reservoirs. This aqueduct, known as the New Croton Aqueduct, was under construction from 1885 to 1893 and was placed in service in 1890, while still under construction… [T]he Aqueduct Commission [then] adopted a resolution for the plans to construct a dam in the Croton River Valley…” and after considerable thought it was decided the most “practicable” solution would be to build “a new and monster dam on the Croton River…” By October 1891 the need was pressing the City suffered a scarcity of water. In 1893 work began on the New Croton Dam. According to The Brewster Standard for March 24 of that year, the project would take seven years to complete and would cost New York City over 4 million dollars. Above the New Croton Dam, other dams would be built: the Mascoot and eventually the Hemlock. It was reported New York City would never suffer a water shortage again. Billions of gallons of water would be kept in reserve at the Croton watershed. However, lives in the villages and towns along the river would change forever.

THE GOOD LIFE

Nothing is known about bottler John Franz’s early life. We do know he came to Croton Falls soon after the Civil War and a few years later opened his bottling works. By all accounts, life was good for John in Croton Falls. In 1891 his daughter was married and the following year John bought a new house. In November John and his wife held a grand ball at their “residence… which was largely attended.” John was considered a man of the best qualities. Needless to says John’s life along the Croton River was about to change. John wouldn’t be the only one impacted by the City’s need for water and the dams being constructed. Ultimately hundreds of families and businesses would be displaced.

CHANGING TIMES

As early as 1893 John Franz and others knew their lives in Croton Falls would someday be much different. Officials were already ordering people to vacate the area in line for a reservoir. That same year a man was “ordered to remove the body of a horse buried two months ago in a field near the Croton.” In addition, the Palmer brothers proprietors of the Hotel Pines Bridge were ordered to vacate. By 1899 John Franz and a dozen others were compensated for the loss of their properties. However, evidence shows Franz and others were far from satisfied with their awards. Eventually, Franz was given more money. Despite this, it wasn’t just his bottling works – a business he had work hard at for thirty years that would be underwater but his beloved new home he had purchased in the early 1890s. Franz, however, wasn’t the only bottler impacted by the dams. Mrs. Thomas Welch owner of Welch’s Bottling Works had, along with other businesses, decided to relocate by moving their buildings to higher ground. We can only speculate but John Franz may have made the decision not to move his home and business simply because he was too old to start new again. He was 62 when ordered to vacate. In 1902 John left his beloved Croton Falls and moved to Mt Vernon, N.Y. Ironically the Croton Valley more than likely supplied Mt Vernon homes with fresh drinking water. In 1904 John visited Croton Falls one last time. By then the landscape must have looked radically different from two years before. Businesses had either moved or had vanished under the rising water. Although none of the stories researched in the Katonah Times or the Brewster Standard specify which dam being built caused John to vacate his home and bottling company we suspect it could have been the Mascoot or possibly the Hemlock Dam. (although the Hemlock was constructed later in the early 1900s.) In 1906 the huge New Croton Dam was completed. It had taken 14 years to finish and had cost over 7 million dollars more than projected. Two years later John Franz, who had been in ill health for some time, died. One newspaper of the time had bitterly charged the commission with taking John’s land and business. Whether John was bitter is not known but more than likely after working and living in the small village 50 miles from New York City (yet not out of its realm of influence) John must have felt some sense of loss. Finally, in an editorial in the Katonah Times, it was pondered whether New York City would pay its fair share in taxes on the large dams it had imposed on the towns and villages in the Croton River Valley. According to Cynthia Curtis, President of the North Salem Historical Society, today New York City “pays a phenomenal amount of money…” to these towns along the Croton River.

LEGACY

Today no one is alive who remembers the stressful times when the dams were built. Today the Croton Water-Shed has some of the best trout fishing in the area. In fact parts of the Croton River still run free and attract many anglers including fly fishermen who catch and release the large trout the Croton has to offer. Though the Croton Water-shed supplies New York City with millions of gallons of water a day, in reality, it still is not enough and the City gets the rest of its water from reservoirs miles away in the Catskill Mountains. In any event, during dry spells villages which were swallowed by the water behind the dams, for example little Sodom, , appear like ancient ruins when the water is low. In fact, if you looked hard enough during those dry summer months you may even find the remains of the Franz Bottling Company peeking above the water. The bottle (above) is a Roorbach soda distributed shortly before John’s business closed. More than likely there are many Franz bottles buried in dumps covered by the billions of gallons of water in the reservoirs. With no way of getting to them, however, diggers like ourselves will just have to make do with what we have.

![]() THOMAS J. FENAUGHTY- DEALER OF SODA, BREWSTER’S FAVORITE SON.

THOMAS J. FENAUGHTY- DEALER OF SODA, BREWSTER’S FAVORITE SON.

If you lived in Brewster during the first quarter of the 20th century and happened to pick up the Brewster Standard you’d more than likely find T. J. Fenaughty mentioned. Fenaughty without a doubt was one of Brewster N.Y.’s most famous citizens. Thomas was not originally from Brewster. Born in Lake Mahopac, N.Y. in 1874 to Thomas and Joanna Fenaughty, Thomas Jr moved to Brewster in 1909. Before the move, though, he had worked in Yonkers as a ticket agent for the New York Central Railroad. But it was in Brewster that Thomas found his calling. Thomas owned Fenaughty Manufacturing Company a bottling firm once owned by the obscure Brewster soda dealer Eugene Connors. Fenaughty was also president of the Brewster-Danbury Motor Bus Company and according to The Putnam County Courier, “a partner in the Dur-Fen Chevrolet Agency“ of Brewster. But Thomas’ professions weren’t limited to buses, bottles and cars Thomas was also involved in a ghoulish but necessary profession- he was Putnam County Coroner! Thomas died in 1934 from a heart attack he also suffered from high blood pressure and diabetes he left behind his wife, Marion and three children. He was 60 years old. The purple bottle above dates to the 1910s around the time he took over the bottling works of Eugene Connors.

We dug this late teens early twenties T. J. Fenaughty from a dump in the Great Patterson Swamp. An unused section of old Rt 22 cuts through the swamp. Along the roadway are two dumps one from the late 1910s the other from the 1940s. After digging both of them this is the only good bottle recovered. There is also a Hemingray insulator dump nearby but everything in it is smashed. The monogram on the front of the bottle ( F. M. C.) is made from taking the first letters from the following words: Fenaughty, Manufacturing, Company.

![]() PIONEER DRUGGIST, W.T. GANUNG AND THE BREWSTER FIRESTORM OF 1880.

PIONEER DRUGGIST, W.T. GANUNG AND THE BREWSTER FIRESTORM OF 1880.

In his later year’s druggist William. T. Ganung was recognized in the Brewster press for owning a prodigious hen and receiving a large pointed gift from Texas, however, 30 years earlier Ganung made news when he and others nearly lost everything in a fire that could have wiped out the tiny village of Brewster. Very little is known about Ganung’s business dealings and personal life. Here’s what Hat City Diggers uncovered: Ganung opened his first pharmacy in 1861. During his career, he had at least two different business partners and at one time or another, both men worked with Ganung in the 1870s and 1880s. His partner A. E. DeForst would be the most recognizable name to Brewster bottle collectors. DeForst would eventually open his own drug firm in Brewster. Needless to say, Ganung had already been in business close to twenty years when on a cold February night George Cree and James Warren, two local man, witnessed what the Brewster Standard described as, “flames leaping through the windows and sides,” of the Lobdell building. The next few hours were nerve-racking as the people of Brewster W.T. Ganung among them tried desperately to save their village from destruction.

THE FIRE

Monday night was like any other winter night in the small hamlet of Brewster, N.Y. 50 miles north of New York City. The only sound heard was the din from a musical reception at Ketchum’s Hall. Then at 10:45 the alarm went out that there was fire! “How long the fire had been burning or the manner of its starting [was] unknown” but by the time the village had organized the fire had engulfed the Lobdell build and was now attacking the four-story brick Robert’s building. W. T. Ganung must have been especially worried his house was only a few doors down from the Robert’s structure. Ganung and other villagers scrambled to save their valuables as a bucket brigade began dosing the burning structure with water. According to the Brewster Standard, the villagers used anything they could to fill with water: “pails, coal scuttles, milk cans and tubs,” In addition to the buckets a relatively new machine was used to fight the growing blaze the horse-drawn Babcock fire extinguisher. As the fire progressed, villagers continued to remove valuables from structures in the fire’s path. Eventually, the Robert’s building’s walls collapsed into a pile of flaming debris then the fire advanced on Ganung’s barn and the nearby hat factory. For a half-hour, villagers worked to save Ganungs residence. W. T.’s barn was burning “fiercely” but eventually the “frame fell in … and the danger was over.” Residence who had removed their valuables from their threatened homes and business to what they thought was the safety of the street now had to deal with another problem: hot embers began igniting their property as it sat in the road. In all, five buildings were destroyed including the hat factory and the town hall and several more buildings were damaged but saved by the villagers and the quick work of the Babcock machine.

AFTERMATH

By morning the fire was out. Two years earlier the lobdell building had caught fire from a carelessly placed lamp in a furniture store but the then the building had been saved. Needless to say, that was not the case in 1880. The fire caused $75000 in damage.W. T. Ganun’s damages were about a $1000 but his home was saved. However, more importantly, the village was spared.

GANUNG THE PIONEER?

Prior to the fire, Ganung appears to have been enamored with the wild west, enough so, that he and his wife spent three weeks in the region in 1870. Eventually, in ads, Ganung would refer to himself as “the pioneer druggist” whether this was a reference to the wild west is not clear. However, Ganung did have friends in the region and one sent William a Texas-sized gift one year. The Brewster Standard reported that Ganung received a pair of steer horns as big as a man- almost six feet across- from The Lone Star State. By this time Ganung was getting on in years but that didn’t keep him making headlines in the Brewster Standard. In the mid-1920s Ganung made the news when his hen -an egg-laying wonder- passed 92 eggs in 105 days… Go figure! We believe William T. Ganung died sometime in the 1920s. We discovered the druggist bottle (above) in a large farm dump in Brewster. The dark substance may be the remains of medicine. Note the nice mortar and pestle graphic common to pharmacy bottles of the time. This bottle has a patent date of 1892.

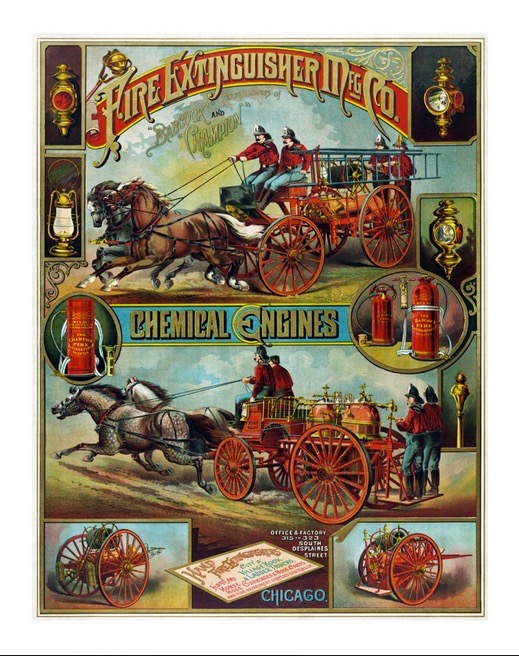

An 1880s ad for Babcock fire extinguisher. One of the machines pictured may have been the type used to fight the Brewster firestorm.

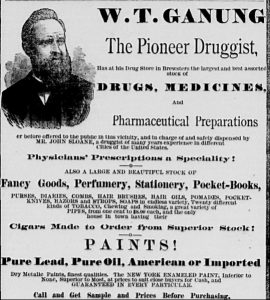

W.T. Ganung “The Pioneer Druggist.” This early 1880s ad from the Brewster Standard contains a drawing of man a who appears to be Ganung.

![]() ALL THE NEWS THAT FITS: THE F. H. MERRITT STORY.

ALL THE NEWS THAT FITS: THE F. H. MERRITT STORY.

If you are looking for biographical information about F. H. Merritt doing a Google search you’ll find none. Although Merritt bottles appear to be common, (there’s always one for sale on eBay- invariably for some outrageous price) facts about this village of Brewster bottler can only be found in the hamlet’s newspaper, The Brewster Standard. And in a close-knit community like Brewster during Merritt’s time where almost nothing really happened, Merritt’s everyday life became front-page news. For example, an 1893 story in The Standard implies Merritt “narrowly escaped serious injury” in an accident that left him with a cut on his ear. And in another write-up, Merritt made news for losing a man’s dog. From the account in The Standard for June 23, 1905. ” Joe Thomas of Danbury recently left two greyhounds in possession of F. H. Merritt of this village and a few days ago one disappeared and has not been seen since. A reward is offered for his return.” In another canine drama reported by The Standard Merritt doesn’t lose a dog but finds one. The tale – pun intended- involved a dog that had roamed from its home in Danbury several miles away. Merritt recused the dog and returned it to its owner. Apparently, Merritt’s health issues also qualified as news in the tiny hamlet 60 miles from the bawdy metropolis of New York City. From two reports in The Standard, the first from Christmas day, and the second from a week later suggests Frank suffered a stroke. Ultimately he recovered. How Frank felt about the media coverage he received during his life is unknown. Trivial matters aside, some of the press on Merritt dealt with his business dealings and at least one story had Frank joining a posse a month after his alleged bout with apoplexy to search for a fugitive. In 1890 The Brewster Standard reported Merritt sold his interest in a beer firm to his partner Wood (Clarence H.) Regarding the same story, The Standard writes that Merritt purchased a hotel in the town of Patterson, N.Y. The Brewster Standard also tells us, in addition to running a bottling business and hotel, Frank also owned a grocery store in Brewster. The February 20, 1901 story concerning the fugitive ends with Frank helping to capture an Italian man, who was involved in a shooting at a hotel in Tilly Foster. In 1908 The Standard had the unhappy task of reporting Frank lost his son, Charles, he was 25. In 1941 under the banner “Happenings of Yester Years” The Brewster Standard reports in a story from 1911 that Frank had died. The Standard writes that Frank was born in White Plains in 1854 and was one of 12 children. The Roorbach (pictured) contained soda. Hat City Diggers recovered it and another Merritt Roorbach from a large farm dump in Brewster. The slug plate contains what we thought was a mistake: an “s” added at the end of “Brewster.” However, we found a few historical references referring to the village as Brewsters. For now, the reason for the pluralization of the villages’ name is unknown. The Bottles from Frank’s earlier partnership with Clarence Wood are especially rare. We have never seen one.

![]() ON BORROWED TIME: THE LIFE OF BOTTLER J.H. COMESKEY

ON BORROWED TIME: THE LIFE OF BOTTLER J.H. COMESKEY

James H. Comeskey, one of Brewster, N.Y.’s wealthiest and best-known bottlers, was also one of the town’s worst drivers not to mention one of the lucky survivors of the most crushing flu ever to ravage the planet. James was born in Torrington, Ct in 1849. Eventually “he settled in Patterson, N.Y. and [worked] as a farmhand…” In 1875 he met Mary Gallagher and they married. The couple lived in the Tilly Foster area named for Tillingham Foster who owned a mine in the district. Sadly Mary died in 1896 at 49 years old. James left Tilly Foster and a short time later opened a bottling firm in Brewster. Comeskey’s business would become one of the most successful in town and eventually, James acquired Putnam House in Brewster and the Lakeside Inn at Tilly Foster. Sources indicate James was living comfortably and by the 1910s, with automobile fever gripping America, James bought, what we believe to be, his first car. Whether James was looking for notoriety is unknown but when he purchased the first Willys-Overland Touring car in Brewster for $750 the Brewster Standard took notice. Without delay James and his car made headlines again this time for crashing it. While driving down the highway James lost control of his Overland, crashed through a fence, careened down a bank and plunged into three feet of water. Luckily he was unhurt. this was not the end of James’ automotive escapades. After the car was repaired James asked the local kids if they wanted a ride in his new car. Packed with children James took off through the New York countryside. It wasn’t long before a crack-up. From an account in the Brewster Standard “While ascending the hill leading to the Port of Missing Men at North Salem… [the car] containing half a dozen children left the road when the steering gear ‘”bound.”‘ The Overland rushed through a grove and “ran up on a stump.” “Mr. C,” as he was called, and children spilled everywhere. James was hurt slightly, fortunately, none of the children were injured. The car was towed into town for repairs. James’ auto antics seemed to be behind him but he wasn’t finished making the papers. This time it wasn’t an auto accident he’d have to live through but the worst pandemic flu the world had ever seen. Historians don’t agree on where the flu originated but between 1917 and 1920 an estimated 20,000,000 people died worldwide. Despite the massive death toll many people survived including this writer’s grandmother, great grandmother and great grandfather and of course James Comeskey who was 69 at the time. The Brewster Standard writes that in 1918 James was suffering from pneumonia without mentioning the flu but more than likely James was dealing with complications from the Spanish influenza virus. James lived through the catastrophic flu and two auto accident but finally, on May 14, 1922, James’ life ended- peacefully- at his home on Railroad Ave in Brewster, N.Y. he was 73. Pictured above (right) is a James H. Comeskey Roorbach soda. The beer (left) is distinctive note the backward J. This bottle was recovered from a farm dump in Brewster the soda was dug from a Roorbach dump in Pawling. Both have condition issues but considering their scarcity, are fine additions to the Hat City Digger’s collection.

![]() WELCH BOTTLING WORKS… WAS THIS TURN OF THE CENTURY FIRM OWNED BY A WOMAN?

WELCH BOTTLING WORKS… WAS THIS TURN OF THE CENTURY FIRM OWNED BY A WOMAN?

Research into the Welch Bottling Works has generated more questions than answers. If John Franz bottles are the most common out of Croton Fall, N.Y., Welch has got to be the rarest. Needless to say, with the help of The North Salem Historical Society, Hat City Diggers has begun to unravel one of the biggest mystery surrounding the enterprise that sold beer in the classy aqua glass bottle (pictured above) 117 years ago.

GENDER IDENTITY

One of the most compelling puzzlers of the Welch Bottling Works story is whether the firm was owned by a man or woman? Evidence suggesting the firm was owned by a woman comes from the 1906 Brewster Standard. In three stories regarding the aftermath of a fire at the Welch Works the paper alludes to the business being owned by “Mrs. Welch” not Thomas Welch (her husband) as expected. From The Standard November 9, 1906: “Mrs. Welsh (sic) is having the foundation laid for a new building to replace the bottling works destroyed by fire.” Then there’s this from a week later: “The foundation for Mrs. Welch‘s bottling works is completed.” The third story is similar to the others and reads as follows: “The bottling works being built by Mrs. Welch has rapidly assumed shape this week. It has been enclosed and the roof is on. F. B. Taylor* will install his machinery as soon as possible.” It seems impossible that The Brewster Standard could make such blatant errors in three different stories in three weeks without a correction.

MORE MYSTERIES, SOME SOLVED?

So it stands to reason, Mrs. Welch was in charge of the business. But what of Thomas Welch. The Answer to this mystery comes from Cynthia Curtis, President of the North Salem Historical Society. In a short telephone interview I conducted, Mrs. Curtis said that Thomas Welch the original owner of the firm may have simple died leaving the business to his wife. This is far from uncommon. When Thomas W. Bartley of Danbury, Ct died in the 1910s his wife Alice Bartley continued the bottling business under her name. Beyond who controlled the Welch Works is yet another mystery regarding the Welchs: Between 1901 and 1902 the Welch house along with several other homes and structures in Croton Falls were moved to another part of town. Why? This puzzler was quickly cleared up by Cynthia Curtis. Mrs. Curtis explains: “The coming of the N.Y.C. water supply system,” Curtis said, “led to the condemnation and sale of acres and acres of property along the Croton River and areas identified for Reservoir construction. Homes and business buildings, barns, sheds, all were either auctioned off [moved]or destroyed.” In the final analysis, although we may have solved some mysteries to a degree of certainty there are still a few mysteries that are unresolved. Two important ones still unsettled are: what started the fire that destroyed the Welch firm and what was the cause of Thomas Welch’s death. With the help of the sedulous work of The North Salem Historical Society’s President, we may soon have these answers.

*In a June 22, 1906 story the Brewster Standard informs its readers that “F.B. Taylor has purchased the Welch Bottling Works[,]” adding to the validity of Mrs. Welch’s ownership.