BOTTLE SHOWCASE- NIGHT SURPRISE!

![]() NIGHT SURPRISE

NIGHT SURPRISE

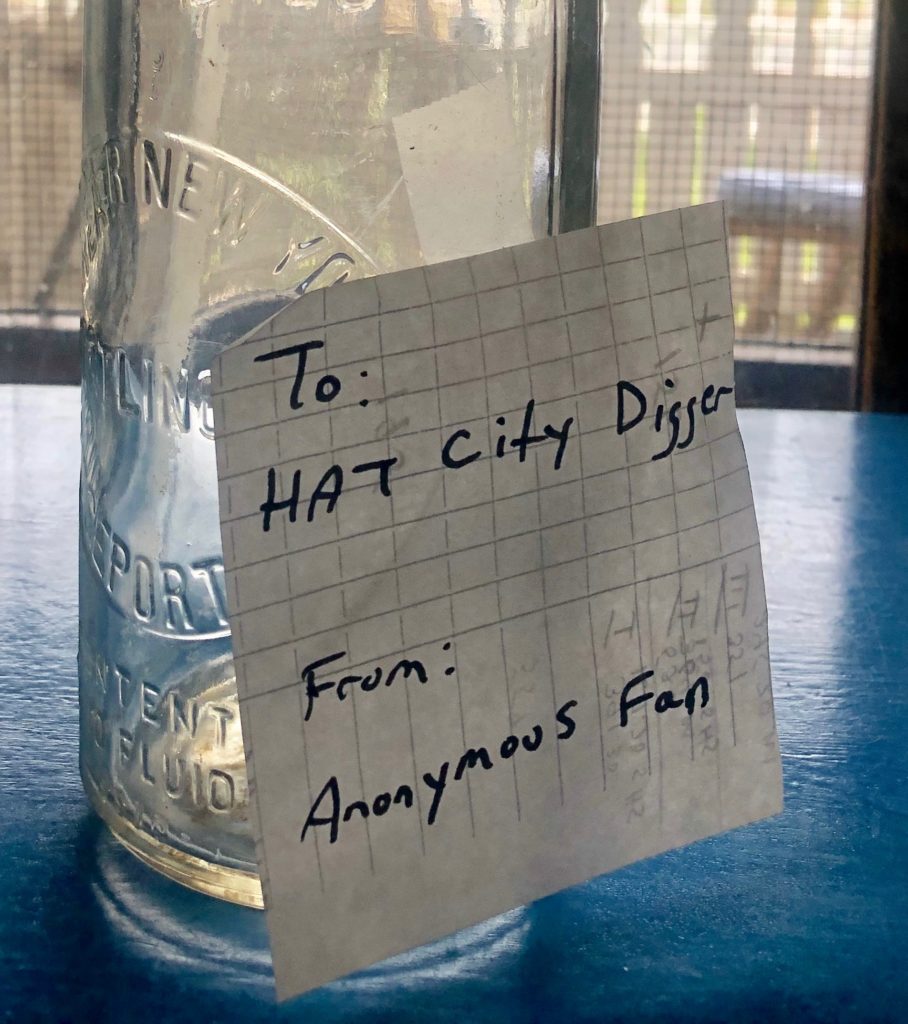

Hat City Diggers received another surprise gift early yesterday morning. Whoever you are we’d like to say “thank you.” The soda is a Fedorko and Son from Stratford, Ct it may date to the 1910s or 20s. We are still learning about this family run business and will update you soon.

![]() FAN MAIL!

FAN MAIL!

Next to digging up antique bottle Hat City Diggers like getting them as gifts and that is what exactly happened today when we found the bottle above on the sidewalk near our headquarters.

The bottle, a very nice Greater New York Bottling Co crown top out of Bridgeport Ct, is a gift from an “Anonymous Fan” Quick research reveals the Greater New York Bottling Co firm was located at 483 Lindley St Bridgeport Ct. Jerome S. Klein owned the firm in the early 1950s but the bottle we received as a gift dates to 1915- 1925. Beyond these limited facts, we know nothing else about this Bridgeport firm. It’s as mysterious as the person that gifted it to us. Finally, Hat City Diggers would like to tip our hats to “anonymous fan” for the great gift on this hot July day. It made our day.

![]() DAMAGED DOOLITTLE

DAMAGED DOOLITTLE

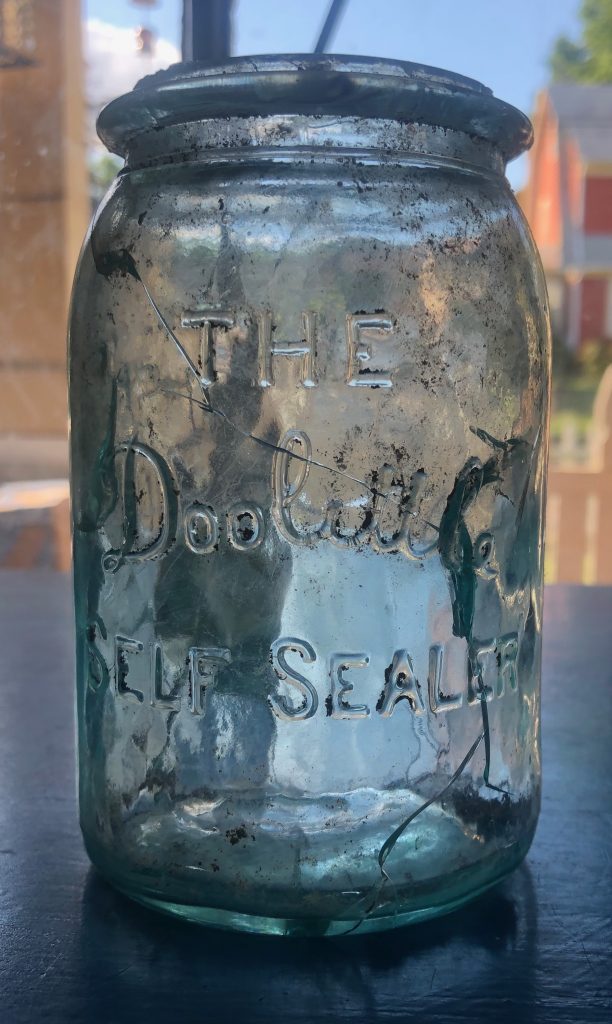

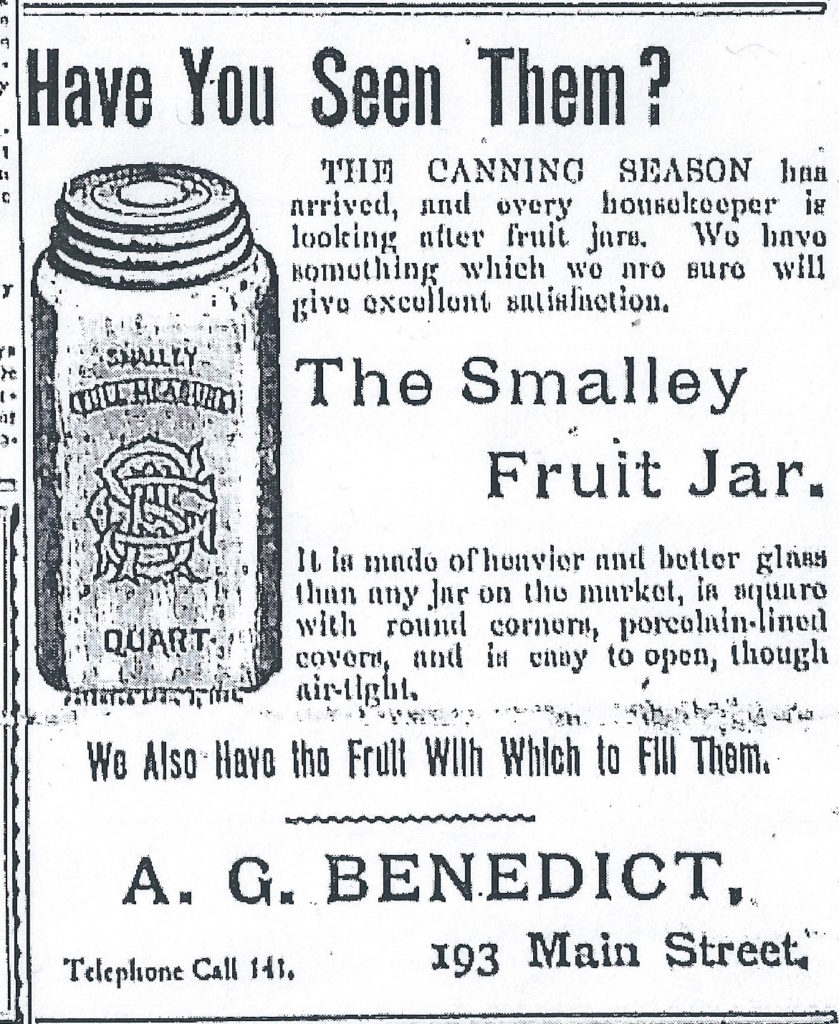

RARE, DEPENDING ON CONDITION VALUE $100+

Sometimes great bottles aren’t in great condition. Take this Doolittle Self Sealer, one of these rare canning jars sold for over $100 but we couldn’t get 100 cents for the fruit jar (above) The Gilchrist Jar Co of Philadelphia manufactured Doolittle Jars. According to a 1900 Doolittle ad in Everyday Housekeeping, The Doo- Little Self Sealer achieved the “highest award [at the] National Export Exposition, 1899.” We recovered our Doolittle from “The Slide Dump” in Danbury.

![]() JULIUS NUSSENFELD JEWISH AMERICAN BOTTLER

JULIUS NUSSENFELD JEWISH AMERICAN BOTTLER

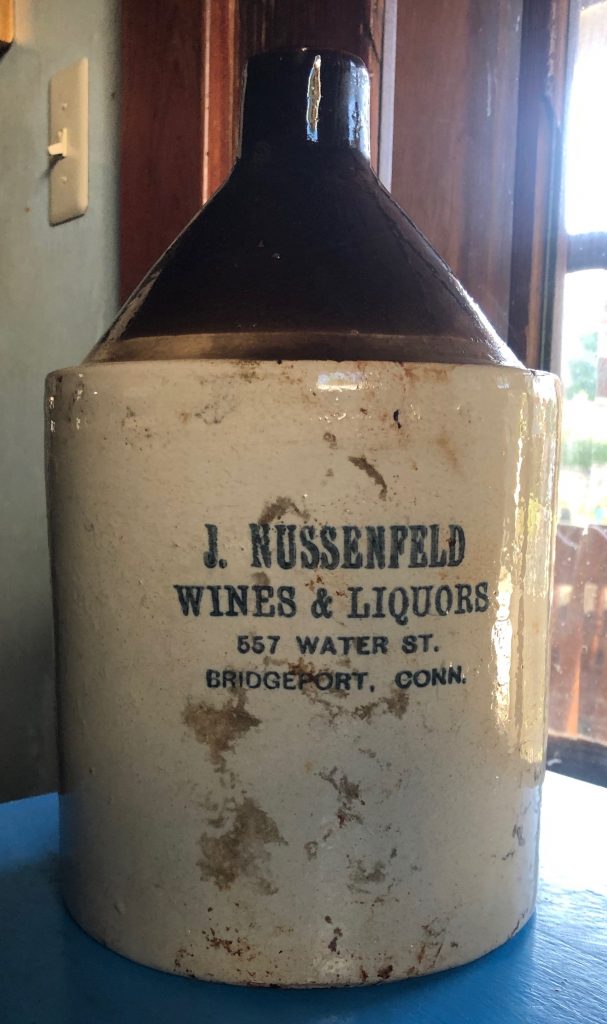

SCARCE, DEPENDING ON CONDITION, VALUE $75+

Julius Nussenfeld ‘s operation was at 557 Water St Bridgeport, Ct. Besides bottling wine and liquor, Nussenfeld was also a developer and landlord, he owned four homes in Bridgeport, In 1912 Julius Nussenfeld planned to build a store and apartments on Main St. in Bridgeport. Julius Nussenfeld’s Tudor style home is listed on the national registry of historic places in Bridgeport. It appears Julius had a daughter, Lillian, who was born in 1897. Julius was a Jewish American. The jug pictured was produced in mass quantity in the early 20thcentury, For the most part, they contained whiskey.

![]() BLACKBIRD RISE- A SMALL HISTORY OF CAW’S INK CO.

BLACKBIRD RISE- A SMALL HISTORY OF CAW’S INK CO.

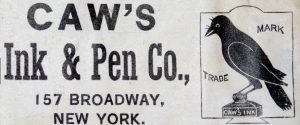

The significant of the crow as trademark for the Caws Ink Co. wasn’t lost by the writers of the January, 1st1896 addition of Printers Ink “The Caw’s Ink and Pen Co, of New York, use a trade-mark of a crow or raven, which at first sight, resembles the Little Liver Pill’s blackbird, but the connection between crow and Caws is obvious.

RECOVERY AND RESEARCH

”When we at Hat City Diggers recovered a Caws from our latest dump we imminently began our research. In today’s world, research can begin instantaneously thanks to smartphones like the iPhone X and we did a search for Caw’s Ink right at the dig site. The hits came quickly and we were instantly enamored with the ink because of its almost story time trademark of an American crow. People just love animals and Caws had other companies beat hands down if you are my age who doesn’t remember Heckle and Jeckle.”Beyond the endearing crow Hat City Diggers’ research revealed a few ancillary details about the long-dissolved company.

WHAT WE LEARNED

The Caw’s Pen and Ink Co was located at 78 Reade Street New York, N. Y. Eventually, the firm moved to 76 Duane St. New York. At some point, the firm was also located on Broadway. The firm even had a location across the pond in London, England. From May 1stto October 30th, 1893 Caws had an exhibit at the World Columbian Exposition in Chicago. During our research Hat City Diggers found that Caw’s main claim to fame was a fountain pen that would not leak (see Caw’s ad) According to American Stationary F. C. Brown was the manager of Caws. Fountain Pen History, Hand and Pen Blog Spot tells us Brown was born in Canada in 185. In 1881 he applied to become an American citizen. By the 1890s he worked at Caws in some capacity. He died in 1925. Caws was still operating at the time of Brown’s death. The ink above is a nice example of a Caws bottle. The glass has a slight aquatint and the bottle shows some real crudity to it and indication it was hand made and probably dates to the 1900s.

The Caw’s Ink and Pen exhibit at The World Columbia Exposition in Chicago.

A Caw’s Ink and Pen Co ad. with their Broadway address listed. Note the crow perched on an ink bottle.

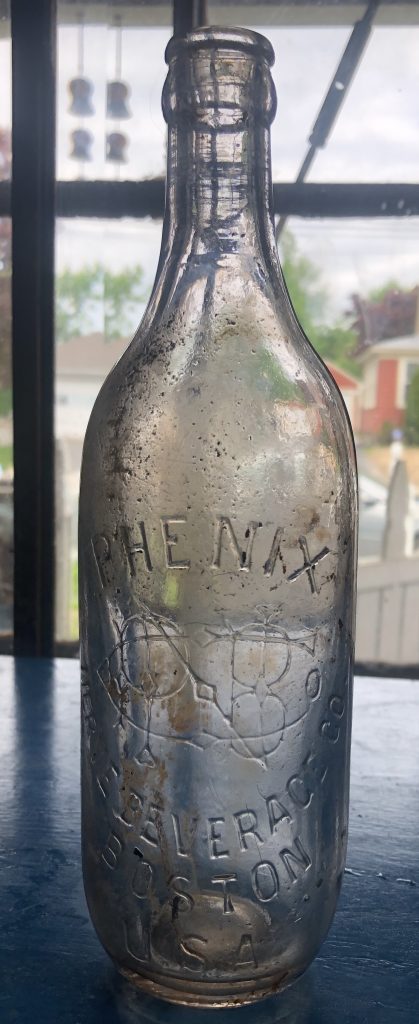

THE PHENIX HAS AROSEN (sic)

Hat City Diggers has dug their first Phenix Nerve Beverage. So far we can find no information on this firm. However, Phenix was a competitor of the iconic Moxie. Whether Phenix tasted better then the famous Moxie is not known.

![]() SOLE PROPRIETOR: A QUICK HISTORY OF THE S. M. BIXBY CO.

SOLE PROPRIETOR: A QUICK HISTORY OF THE S. M. BIXBY CO.

Contrary to popular belief the S M Bixby Co did not produce writer’s ink they made shoe polish. The Bixby Ink story is one of rags to riches. When S M Bixby arrived in New York in 1858 he was according to the Cyclopedia of American Biography By James E. Homans “nearly penniless.” Dissatisfied with the west Bixby had left Cedar Rapids IA after selling the general store. Bixby, however, was not from Cedar Rapids he was born in 1833 at Haverhill N. H. According to James E. Homans Bixby’s mother died soon after Mr. Bixby’s birth. “In 1848,” According to Homans, “he went to Boston walking a good part of the way…” and found employment at a men’s furnishing business… “ which he… purchased.” Bixby hated the climate in Boston so he packed up everything he had and moved west. Eventually finding his way to Cedar Rapids. Now in New York, he had nothing but an overpowering drive to succeed. At first, he peddled goods for a store then worked his way into a position at the firm. Homans reports Bixby eventually “ went into the shoe business with a roommate. Bixby bought the shoe store and in 1860 he began making and selling shoe blacking the business was a success and by 1865 Bixby sold the shoe store and concentrated on manufacturing and selling blacking. According to James E. Homans Bixby’s capital was about $30,000. He needed money for advertising and experiments and equipment and the proceeds of the shoe store didn’t last long. He admitted partners but Homans relates that the struggle for success was severe. “[N]ot until after many years of persistence” was Bixby able to turn a profit. In 1876 Bixby made a great effort to show his product at the Centennial Exposition but the cost was great and the business failed. Then according to Homans two years later with only $75 and with no partners Bixby finally succeeded. “The business… increased” reports Homans [and] eventually [it] reorganized as a corporation in 1898. S. M. Bixby remained president until 1909 when he retired. Samuel Marrill Bixby died on March 11, 1912, in New York City.

Some of S. M. Bixby Co products [like]“Three Bee” Blacking and “Royal Polish” according to The King’s Handbook of New York “[are] …a blacking paste for men’s boots, and a liquid dressing, for restoring the color and gloss to ladies’ and children’s shoes.” Hatcitydiggers.com is not sure if the bottles above contained paste or liquid. The amber bottle (left) may be scarce. The firm was located at 194 and 196 Hester St in New York City. The King’s Handbook reports that the salesroom and offices were on the second floor. The Bixby firm employed about 150 people. In addition to Samuel Bixby producing shoe blacking in the early days of the firm, Samuel arranged music. One song Little Dicky-Bird was copyrighted in 1892.

The Bixby firm in New York.

S. M. Bixby.

![]() DRUNKEN MONKS: A SHORT HISTORY OF SALVATOR BEER

DRUNKEN MONKS: A SHORT HISTORY OF SALVATOR BEER

With Lent fast approaching Hatcitydiggers.com feels it is appropriate to profile the long forget beer of that Christian season. According to Pure Products Vol 9 1909, Salvator Paulist Monks originally brewed the beer starting in 1623. Other sources tell us the Monks drank the beer for nourishment during their 46 days of fasting during Lent. Salvator means savior and the beer is rich in sugar making it much sweeter than other beers so it is easy to imagine the German Monks with their empty stomachs getting soundly crocked on the sugary brew. The tradition of Salvator beer became more secular in the 19thcentury. A report in On Beer: A Statistical Sketch tells us that according to tradition “The first glass of “Salvator” is drunk by the Burgomaster of Munich, who according to old usage, should be on horseback.” It is unknown if the Salvator Brewery of Philadelphia was brewing the sweet beer only over Lent or whether the firm was making and selling its stock the entire year but needless to say, the firm appears to have had a short life span opening and closing its door within a few months. Consequently, this short window suggests that items associated with the brewery such as the bottle pictured are rare. The firm’s proprietors were Eick and Pulaski. They appear to have closed the firm in 1889. Hat City Digger discovered this beer in a Connecticut dump. As you can see the neck and finish are missing yet because of this beer’s rarity Hat City Diggers added it to their collection.

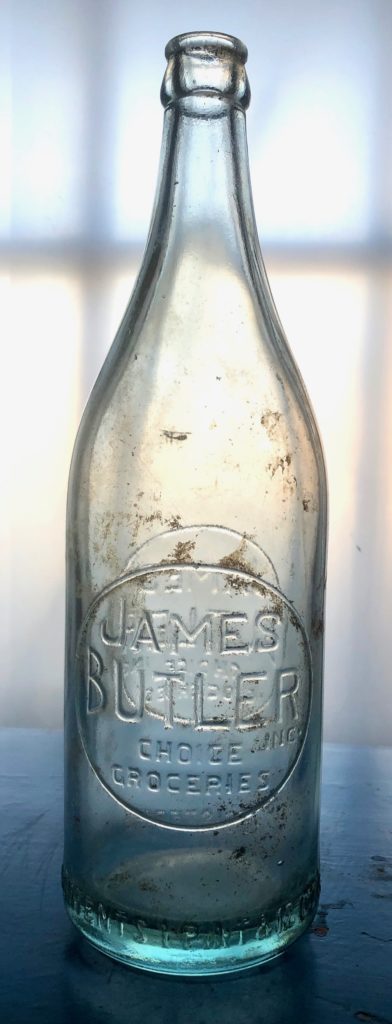

![]() THE BUTLER DID IT

THE BUTLER DID IT

Before Danbury had Stop & Shop or Shop Rite. The Hat City was home to a host of markets and grocery stores one such firm was James Butler Grocery Inc. The first entry for the firm appears in the 1926 Danbury City Directory. According to Michael Wilson a Danbury historian “[This] would put it in the fairly new (1922 or 1923) Pershing Building.” By 1930 Butler had two locations one at 192 Main St (the original location) and one at 93 White St. The building for Butler’s White St location no longer exists according to Wilson. Hat City Diggers has excavated several early twentieth century dumps in the Danbury area and this is the only Butler bottle we’ve recovered. We feel the bottle pictured dates to the 1920s. The aquatint in glass was being fazed out by then so the Butler bottle’s color is quite light. James Butler died in 1934.

![]() CLEAN MACHINE

CLEAN MACHINE

Was the title of an obscure Woodie Guthery song inspired by the name of a rare cleaning product? Hat City Diggers recovered the emerald green bottle pictured above from a dump in Danbury. Since then it has remained an enigma. We have never found a single scrap of information on this bottle that is embossed with the singsong name Clean-O. It appears that no other example of this bottle exists. Although this is not likely, nevertheless, to date an uploaded image to US Bottle Diggers and Collectors has not produced a single response. Oddly a clue to the product’s existence may actually exist and it comes from an unlikely source. In 1946 the famous folk singer and musician Woodie Guthery recorded a song. Intriguingly he called the song Clean-O. Guthery’s tune is obscure and has no Wikipedia entry and Hat City Diggers can find no history on the song from internet sources. Although not a clear cut reference to Hat City Diggers rare bottle, the title of the song is written the same way as the product’s name, that is, with a hyphen between the N and O. Like John Lennon who borrowed words for “Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite” or Jim Morrison who took lyrics for “Celebrations of the Lizard” from James Frazer’s Golden Bough, Woody Guthery could have taken the titled his song “Clean-O” from the name on our rare bottle. We can only speculate. For those who may be interested in knowing the contents of Clean-O Hat City Diggers has a theory: During our adventures, we have discovered many bottles of a similar shape and most have contained laundry cleaner mainly bleach. Finally, one day we may find information on Clean-O but for now the product remains a mystery all we have is its name, a possible Woodie Guthery refinance, and the product’s jingle: “Clean-O Cleans, Clean!”

![]() WAINWRIGHT’S TUNA

WAINWRIGHT’S TUNA

If Ace Ginger beer is one of the most common ginger beers, then Star Brand Old English Style Ginger Beer has to be one of the rarest. And Hat City Diggers has just acquired one. Nothing is known about Star Brand other than it was put out by the Star Bottling Works of Philadelphia. This information comes from the bottle. Star is one of the most common names in bottling. Hat City Diggers acquired the emerald green beauty (pictured) from Barry Wainwright a Digger in New Jersey. Barry has been digging for years and this is the first time he has seen this bottle. Barry recovered four of the green bottles from a dump he’s digging. Hat City Diggers traded for the bottle which has a 7-ounce capacity and dates to the late 1910s to mid-1920s. The bottle is very similar to the Ace bottle except for the color the Ace is brown. As far as Hat City Diggers and Barry Wainwright know, Star Brand Old English Style Ginger Beer is an exceptionally rare find. Hat City Diggers can find no known examples of the Star bottle other than the four Wainwright found.

![]() NOT IN KANSAS ANYMORE

NOT IN KANSAS ANYMORE

Pawling, New York is a long way from Topeka Kansas, nevertheless, this Roorbach soda was recovered from a dump in the sleepy New York village 15 miles from Danbury, Ct. How a bottle from Kansas made it to New York is unknown, regardless, this A. L Snyder is now in the permanent collection of Hat City Diggers. Information is limited about Snyder and what we do know comes from the Topeka City Directory and Jim Eifler a regular contributor to the Facebook Group US Bottle Diggers and Collectors. According to Jim A. L. Snyder was born in Pennsylvania in 1857. At some point, he made it west and settled in Topeka, Kansas. The 1880 Topeka city directory tells us A.L. Snyder was the operator of the Enterprise Hotel in Topeka at the corner of 4th St and Washington Ave. A. L.’s brother (only initials are given for the siblings’ first and middle names) E. T. is listed as a baker at the hotel. Jim, referencing the directories, tells us that in 1882 A.L. and E. T. were partners in a baking enterprise called Snyder Bros. located on Kansas Ave in Topeka. By 1887 the brothers not only are listed as bakers but also grocers. And in 1888 the directory lists Snyder’s bottling works at 310 Kansas Ave. Eventually, E. T. is no longer listed in the city directories possibly because he died or moved. According to Jim Eifler A. L. Snyder died on August 4, 1897. At face value, the Snyder bottle appears to be rare and may date to the 1880s.

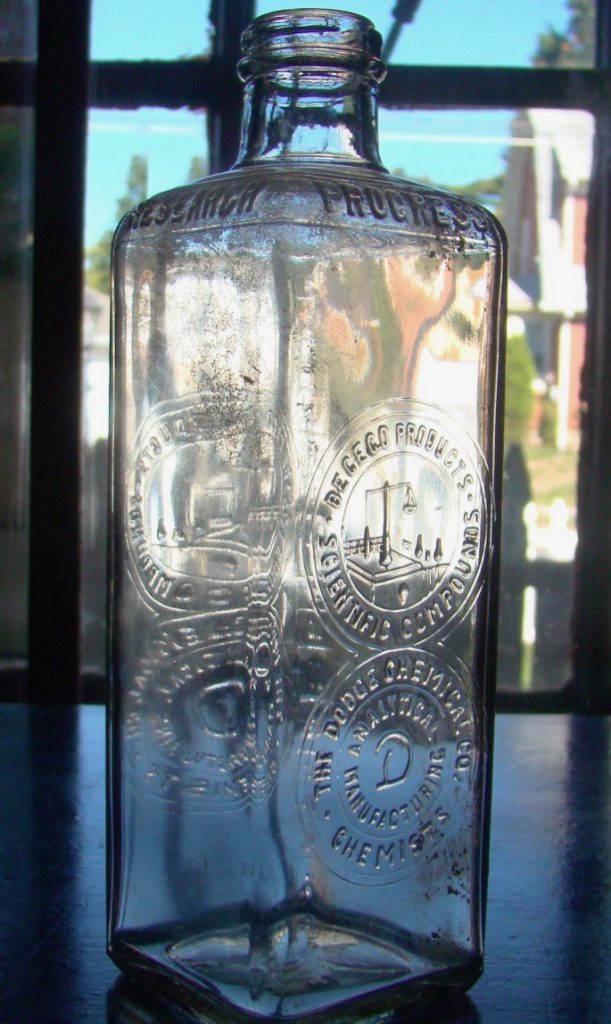

![]() DIGGERS’ PUZZLE MAY HAVE BEEN SOLVED

DIGGERS’ PUZZLE MAY HAVE BEEN SOLVED

Hat City Diggers may have finally solved one of their most challenging mysteries. At several dig sites, the diggers from Danbury found embalming bottles. “We knew we weren’t digging in the back of mortuaries or morgues so finding these bottles was pretty puzzling,” said Hat City Diggers. So what would ordinary people need with embalming fluid?

At first, the diggers proposed that people were using the chemical to embalm their pets “People will embalm pets to bury with dead loved ones- the Egyptians buried embalmed animals with the pharaohs” said the diggers. The diggers also speculated that people were preserving animals as wet specimens, that is, embalming the animal with formaldehyde and preserving the specimen in a jar containing alcohol. Although these theories are fair in their own right, the real reasons why people used embalming fluid or formaldehyde as it’s called 80 and more years ago will surprise if not shock you. Hat City Diggers found the answers in turn of the century medical books. According to these very brittle 100 plus-year-old books formaldehyde could be used as an antiseptic not only to clean sickrooms but also in cases of blood poisoning injected into the sick person’s body! From one of the journal comes this excerpt which defies common sense. “[formaldehyde is a] swift and sure destroyer of infusorial life… killing or checking the growth of all the low forms of animal and vegetable life… formaldehyde is found to be an effective preventer and destroyer of blood poisoning…” The medical journal recommends that treatment be carried out by “an injection into the veins of, say the arm, a one-pint solution, and closely observing the results before repeating the operation.” “This is a case where the cure could definitely kill you.” said Hat City Diggers. “Just think, they wouldn’t have to embalm you after you died because they did it to you when you were alive!” The family medical books also recommend formaldehyde to treat consumption, influenza, “all zymotic diseases and is especially valuable in the prevention of smallpox.” “These books have been in our family for years.” said Hat City Diggers, “it’s a wonder any of our relatives survived!” The embalming bottles (above) from the ESCO firm date to the 1930s or 1940s likewise the Dodge Chemical bottle (below) dates to the 1930s or 1940s. ESCO and Dodge Chemical are still in operation today.

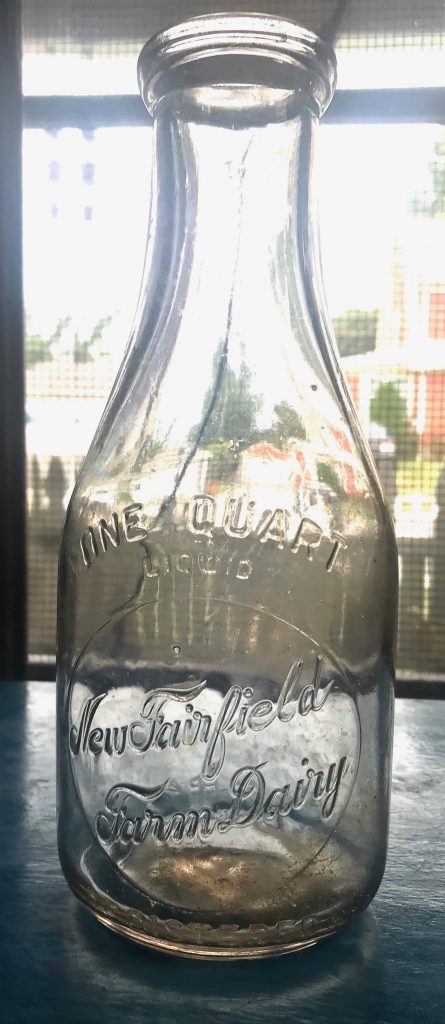

![]() NEW FAIRFIELD FARM DAIRY

NEW FAIRFIELD FARM DAIRY

100 years ago Danbury City Directories listed hundreds of farms in the area. Today only a hand full exist. It’s the same in New Fairfield a town that borders Danbury on its north side. Vestiges of farmland remain in New Fairfield. One can still be seen on Bigelow Rd once home to the New Fairfield Farm Dairy all that remains of the farm is its large white silo. Today houses dot and streets intersect the land that was once pasture and meadow. Hat City Diggers recovered the milk above from a dump we were digging in Beaverbrook. It may date to the 1930s or 1940s. According to one source, the dairy was still operating in the 1960s. Beyond this limited information, we know nothing else about this New Fairfield, Ct enterprise.

Because information is very limited on the New Fairfield Farm Dairy, when this milk jug showed up at our headquarters we were pleasantly surprised. Although the embossing on the body of the jug says Brock Hall Dairy the lid is clearly embossed “New Fairfield Farm Dairy Conn” proof of the dairies existence in Ct.

![]() U.P.T. CO A COMMON BOTTLE WITH AN AWESOME TRADEMARK

U.P.T. CO A COMMON BOTTLE WITH AN AWESOME TRADEMARK

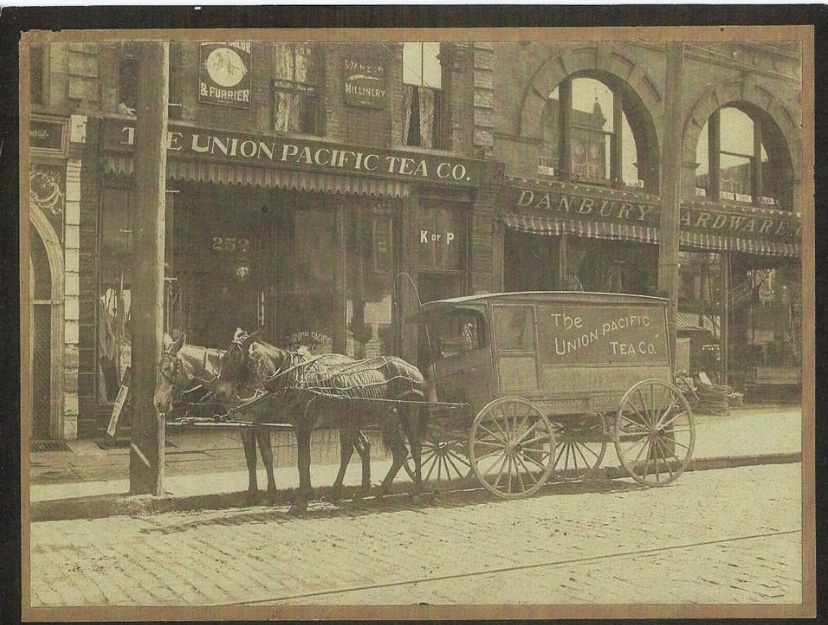

Rival to A & P the Union Pacific Tea Company had stores across the eastern half of the USA at the turn of the century including one in Danbury, Ct. on Main St. The companies headquarters was in NYC. The firm is known today only because of their advertising cards and other ephemera. HatCityDiggers.com found very little about the firm after conducting an Internet search. The companies trademark is bang-up, though. It depicts a mahout (sometimes two at times none) riding an elephant. The Grand Union Tea Co. swallowed the firm in the 1920s. The bottle pictured dates to the turn of the century.

A horse and mule delivery team parked outside The Union Pacific Tea Co. on main St in Danbury ca 1900. (Photo, Bob Brought Jr)

![]() LOUIS LIGGETT- “THE DRUG KING” THE RISE AND FALL OF THE UNITED DRUGS EMPIRE

LOUIS LIGGETT- “THE DRUG KING” THE RISE AND FALL OF THE UNITED DRUGS EMPIRE

Today we take drug store chains for granted. Everyone’s heard of CVS, Walgreens and Rite Aid. At the turn of the century, however, the idea of large drug store corporations was unknown until one man living above a saloon had a vision. And his dream started with nothing more than $150. The Pharmaceutical Era for December 1916 reports that Louis K Liggett was born in Detroit, Michigan in 1875. He attended school in Detroit until he was 14 then began a short career as a traveling salesman. Ultimately, Louis found himself working as a drug clerk and according to Joseph F Preston writing for The Magazine of Wall Street Louis was out “grubbing along on a drug clerk’s salary… married and living [in a low-cost rent] somewhat down on his luck.” Liggett was unhappy Preston says, working as a soda jerk and living in a run-down tenement above a corner saloon. Joseph Preston describes Louis Liggett as getting mad. Preston’s colorful story paints a picture of Liggett awake at night reclined in bed scheming and planning ways to better himself. One morning, as the story goes, Louis K Liggett told his wife that if he had to beg, borrow or steal he’d get $150 and move to Boston “where new ideas, so he had been told, were worth big money.” According to Preston, Louis didn’t resort to robbery he borrowed the money “and hit the trail for Boston.”

LIGGETT’S DREAM COMES TRUE, THE BIRTH OF REXALL AND UNITED DRUG COMPANY

Louis K Liggett had a big dream. a cooperative of drug stores stretching across the length and breadth of the USA and in 1902 he made big strides toward reaching that dream. According to an article in The Magazine of Wall Street written by Benjamin Graham, Louis Liggett started with 40 retail druggists in 1902 under the United Drug Company. United Drug would manufacture merchandise and sell it at retail drug stores which would be called Rexall stores. (Today Hat City Diggers find the artifacts associated with Liggett’s dream. In several Danbury area dumps, we have unearthed Rexall and United Drug Company bottles.) Rexall means “king of all” and that’s what Louis K Liggett had produced. According to Preston in his article for The Magazine of Wall Street here’s how Louis’s idea worked. Preston reports Louis Liggett convinced small city and town pharmacist who ran family-run businesses that they were overworked. In so many words Liggett said join our cooperatives we’ll build a factory manufacture all the medicines in Boston all you have to do is sell it at your shops. I’ll improve your profits and bring prices down. It was a win-win situation. The only problem, Liggett had nothing more than the $150 he borrowed in Detroit. Nevertheless, the charismatic Liggett persuaded the druggist with- as what Preston called “the right dope” it was so plausible that these druggists couldn’t believe no one had thought of it before. In no time Liggett was manufacturing the medicines in Boston and sending them to all the Rexall stores “and the Rexall stores were operating at full steam.” In a few short years, Liggett had built an empire with Liggett and Rexall stores across the USA. Eventually, there would be more than 7000 Liggett and Rexall throughout the USA. Liggett had achieved his dream. Then Liggett’s massive empire was knocked to the mat.

LIGGETT LOSES CONTROL

In 1921 the bottom fell out of Liggett’s vast empire. In a matter of hours, United Drug’s stock plummeted from a high of 175 to a low of 54. “The Drug King” lost millions. More than $5,000,000 according to Drug Trade Weekly. And Liggett according to Drug Trade Weekly was the cause. The days up to the crash Liggett was accused of gambling in the market also, United Drug had agreed to float a loan of $15,000,000 and Wall Street had been a flood with rumors which imparked Liggetts stock. Because of such a substantial loss the Drug King, as he was called, was forced into Trusteeship and he lost control of his assets. Liggett and Rexall firms were assured the corporation was as solid as a rock. The National Magazine of that year reported Liggett’s followers had a personal loyalty and faith in their leader. Nevertheless, over time the Liggett empire shrunk. Liggett went bankrupt in 1933.

THE END

After years of operation, the Liggett store on Hayestwon Ave in Danbury closed its doors in the early 2000s. Liggett’s stores had been closing across the USA for years. If memory serves me right Liggetts in Danbury was the last Liggett’s pharmacy in the Danbury area. Rexall stores in Danbury had gone out years earlier. Rexall business ended in the late 1970s One of the best known Rexall stores was Burn’s on Keller St. Louis K Liggett, The Drug King died in in 1946 he was 71. At one time Louis’s kingdom consisted of over 7,000 stores. Today Rexall products are only found at Dollar General in the USA. According to The Rexall Story, A History of Genius and Neglect Rexall was a “brilliant and successful business/pharmacy venture [that] was allowed to fail through carelessness and an inattention to the original formula of the company.” A formula created by the Drug King, Louis K Liggett.

REXALL RULES

During the firm’s height, there were thousands of Rexall Pharmacies across the USA selling patent medicines toiletries and more. Mahoney and Burns had two stores in Danbury according to this bottle from the 1910s.

![]() DRESSED FOR SUCCESS

DRESSED FOR SUCCESS

One of the best-known salad dressings of the 19th and early 20th centuries was created by a man who intermarried in 1849 a year before he founded his famous enterprise. The Eugene R. Durkee company began as a spice company in 1850 but in 1875 because of America’s interest in salad dressing, Durkees started producing dressing made from egg yokes and oil in small bottles. According to Food and Drink in America: A “Full Course” Encyclopedia Durkee’s dominated the market for four decades because of an intense ad campaign. By 1915 Durkees held six patents on a range of products including celery salt, flavoring extracts and of course salad dressing. Eugene Durkee died in 1902. Mrs. Durkee died in 1889. Today Hat City Diggers finds Durkee’s Salad Dressing bottles in abundance in the Danbury area. We discovered the one pictured above while creek walking.

![]() FROM THE BRASS CITY…

FROM THE BRASS CITY…

1928 saw the formation of the Brassco Bottling Company out of Waterbury, Ct. According to Jim Eifler a contributor to U.S. Bottle Diggers and Collectors the firm location was on East Liberty St in the Brass City. Bronis Karpovich was the firm’s president and Nellie Jenusatis vice president. Peter Drevinskas was secretary and treasurer. The firm closed its doors in 1959.

![]() CUCUMBER FACIAL- A REALLY SHORT HISTORY OF CASWELL & MASSEY

CUCUMBER FACIAL- A REALLY SHORT HISTORY OF CASWELL & MASSEY

It’s been said the Divine Sarah Bernhardt loved this face cream. The famous actress used it often. According to the American Druggist and Pharmaceutical Record Caswell, Massey & Co was founded in 1780 by Charles Feke. Over intervening years several proprietors owned and operated the firm then in 1876 William M Massey joined John R Caswell forming what is now known as Caswell and Massey. The firm is still in existents today. The jar above isn’t from the 1700s though it probably dates to the 19th century.

![]() SOJOURN TO SAUGERTIES PRODUCES RARE POISON

SOJOURN TO SAUGERTIES PRODUCES RARE POISON

Hat City Diggers latest adventure in Saugerties N.Y. ended with the recovery of a rare cobalt poison. We uncovered this exceptional bottle (pictured above) after about 30 minutes of digging. To say we were excited is an understatement. At first, we thought it was slick but when we turned the bottle over we got an eye full of embossing. AMB poisons like this blue beauty held mercury tablets which were used as an antiseptic. Not only was the disinfectant deadly to germs it was also a proven killer and mutagen in people.

Blue gold from Saugerties.

![]() PISO’S CURE: EVERYBODY MUST GET STONED!

PISO’S CURE: EVERYBODY MUST GET STONED!

Piso’s Cure for Consumption was one of the most popular nostrums in America during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Based on the number of bottles Hat City Diggers finds in Danbury- and if Danbury, Ct represents a cross-section of the U.S.- a large portion of America must have been getting totally baked on the cannabis concoction that made up Piso’s Cure!

HIGH TIMES

Over a hundred years before medical marijuana became all the rage, cannabis was legal and found at every pharmacy in the U.S. and Danbury pharmacies were no exception. More than likely a person could walk into any of the pharmacies on Main St. and White St. in the Hat City. and for 25¢, more or less, buy some kind of potion fortified with Mary Jane. But by far the most popular elixir to contain weed was Piso’s Cure for Consumption.

HOMEGROWN

Ezra Taylor Hazeltine. gets most of the credit for creating the Piso brand- the company bore his family name. Ezra, however, did not start off in the patent medicine trade, in fact, he didn’t even invent the nostrum- just its name. According to Genealogical and Personal History of the Allegheny Valley: “[Ezra] began his active career as a teacher… [and worked]… in… Pennsylvania, Iowa and New York.” For reasons unknown, he quit teaching and by 1860 he moved to Warren County, Pa where he took a job as a clerk at the family pharmacy. Ezra did develop his own nostrums during this time but according to Piso’s Trio: One Step Ahead of the Law by Jack Sullivan, Ezra’s partner “Dr. Macajah C. Talbott, a medic and wannabe snake oil salesman who was also new to Warren, Pa developed Piso’s Cure. Even so, it was Ezra who was the marketer, yet precisely how Ezra Hazeltine originated the name Piso is unclear. In addition, Talbott’s development of the concoction is also lost. What we do know is that the formula at some point was “discovered” by Talbott. Needless to say, what is known is “Whether because of price or advertising, sales of the nostrum rose rapidly and attracted a national customer base.” and by 1870 the company built a factory in Warren, Pa. Although Piso’s contained weed from the start, the cure also harbored a host of other drugs that if taken regularly could easily lead to addiction. These drugs: Opium and other morphine derivatives were removed but 420 remained.

BUMMER ROAD, REEFER MADNESS, BURNOUT

BOTTLE VARIANTS

Pictured above are four variations of Piso’s bottles during different stages of the companies life. The second bottle from the left is the oldest it’s embossed with the word, “consumption”. The amber Piso’s with the finish similar to a “Priof” top dates, we believe, to the late 1910S. The emerald green bottle left has the words “Piso’s Cure” embossed on a side panel which suggest this form was made before The Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906. The green Piso’s (right) may date between 1908-1912 and does not contain the word “cure”.

![]() WANTED: CALIFORNIA POP BEER!

WANTED: CALIFORNIA POP BEER!

Collectors of New Jersey bottles are passionate about their hobby and one of the prizes to any collection is C. C. Haley’s Celebrated California Pop Beer. (It seems even in the 19th century California had a far-reaching appeal). Ernest Bower “a longtime New Jersey digger and collector,” wrote the book on Haley and his bottles. According to Bower, there are at least four variations of the Haley & Co California Pop Beer bottles. The Haley’s pictured above is the one most frequently seen. In addition, California Pop Beer was also sold in amber blobs and stone beers. The “hutch” style bottles are the ones most sought after by collectors with the patented stopper bottles being the most desirable to all collectors of beer and soda bottles. Inevitably collectors ask the question Where did Haley come up with the name Pop Beer? The answer is not an easy one but it may have something to do with the sound the stopper made when it was removed or pushed into the bottle when filled with the highly carbonated liquid. Another likely answer has to do with the meaning of “pop” which suggests nonalcoholic carbonated liquid which Pop Beer was. The crude embossing on the Haley’s (above) suggests the bottle dates to the 1880s.

![]() TRUTH IN ADVERTISING -T. J. STONE SODA

TRUTH IN ADVERTISING -T. J. STONE SODA

Sounding more like a Tom Selleck character then a bottler Thomas. J. Stone of Torrington produced beer and soda in the Berkshire hills town for years. Although an internet search produced a few hits on Stone bottles little is known about the bottler or his enterprise. Hat City Diggers discovered the soda (above) in New Milford, Ct. and we were immediately charmed by it. But beyond the color and whittling of the glass This Stone bottles most appealing quality is the phrase at the bottom of the slug plate, “Artificial Color & Flavor” Contrary to popular belief artificial additives in foods is not a 20th century invention, in fact, artificial flavors were in widespread use in the late 19th century. After the Pure Foods and Drugs act of 1906, producers of foods, patent medicines etc were forced to be more candid in marketing their products. By the 1910s sodas like this T. J. Stone were labeled with the capacity. However, Stone went a step further by telling his consumers his product contained artificial additives. There may be other bottles with similar embossing but Hat City Diggers have never encountered one making this soda quite rare- at least to the Danbury area. Stones’ business was located at 168 Migeon Ave. in Torrington.

![]() THE POTASAFRAS CO.

THE POTASAFRAS CO.

Patent medicine companies are famous for their peculiar names but this firm takes the cake. If your first thought is potato, you are dead wrong- think more in the line of potassium iodide. However, we doubt the firm was adding bananas to this 1914 nostrum. Potasafras was the brainchild of H. W. Campbell. Campbell appears to have had a reputation as a real snake oil salesman. According to the Journal of Outdoor Life Campbell ran a company called Natures Creation in the early 1910s that claimed its products could cure everything from TB to syphilis. The journal called out Campbell as a quake in an expose′ it ran in 1912. That appears not to have stopped Campbell because according to the bottle (above) he started the Potasafras Company a few years later in 1914. Instead of VD Potasafras was used to treat asthma. Records indicate the company was still in business in the 1930s. We dug the bottle (above) from a dump we discovered during a trip to Saugerties, N.Y.

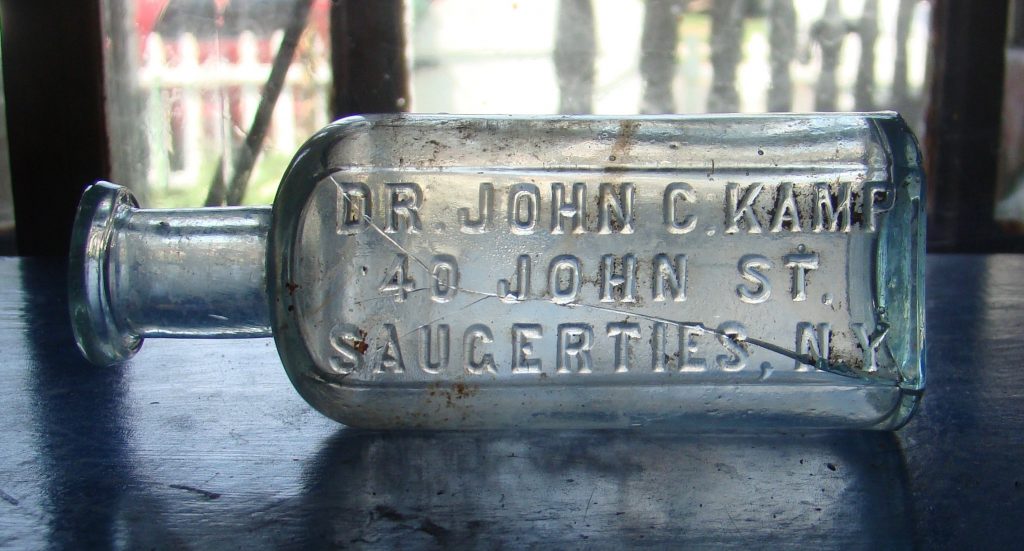

![]() A COUNTRY DOCTOR, JOHN CHARLES KAMP.

A COUNTRY DOCTOR, JOHN CHARLES KAMP.

Dr. John Kamp had a $6500 mortgage on his home and worked 60 hours a week 52 weeks a year caring for the villagers of Saugerties, N.Y. The year was 1940 and John, 80 years old, showed no signs of slowing down. Dr Kamp was not native to the village he came to Saugerties from Buffalo, N.Y. in 1916 when he was 56 years old- already an old man by early 20th century standards. John was originally from Wisconsin and his parents were from Germany. When Dr Kamp reached Saugerties, he bought a house at 40 John St in the village and opened a practice which he continued for the next 20 years. Not only was Dr Kamp in private practice he was also Saugerties Health Officer. and over those years of public and private service, he became one of the villages best-known citizens. However, John wasn’t the only Kamp who built a respected reputation in Saugerties. Dr. Kamp’s wife Mary become one of the areas best-loved artists. Dr. Kamp died in 1944. We found the bottle (above) which was made during WWI during our third trip to the village. Unfortunately, it is severely cracked. Nevertheless, it is proof Dr. Kamp was mixing his own potions and administering them to his patients in the tiny village along the Hudson.

![]() LOVE IS BLUE.

LOVE IS BLUE.

Although damaged, this ice blue Coca Cola still displays nicely. Rare, ice blue Cokes can fetch over $100 at auction. New Milford, Ct is the only town where Hat City Diggers finds this variant of the iconic hobble-skirt bottle. Though no city is listed on its base, this bottle may be from the Bartley and Clancy bottling works of Danbury. Bartley and Clancy had the contract to bottle Coca Cola in the 1910s. The Variant (above) is a 1915.

![]() THE DEMOLITION SITE PRODUCES ANOTHER SPECIAL FIND.

THE DEMOLITION SITE PRODUCES ANOTHER SPECIAL FIND.

Over the winter Hat City Diggers began excavating a demolition site. The building at this  undisclosed location was razed and under its foundation is an 1870s trash pit. We’ve pulled several very old bottles from this site and the Everhart blob pictured is no exception. William Everhart started his “bottling house” in Easton, Pa. in 1877. Everhart bottled an assortment of beers, such as lager, porter and ale. He also bottled mineral water and soda. The bottle (above) is a soda that contained about six ounces of liquid- scarcely a mouthful by today’s standards. Everhart’s business was located at 12 North Fifth St in downtown Easton. According to an 1881 write-up in Manufacturing and Mercantile Resources of the Lehigh Valley William Everhart “built up a large trade in Easton and its neighborhood…” In addition according to the review, one of Everhart’s specialties was birch beer which was “highly prized” by the community. Today Everhart bottles sell for around $10. Currently, we have no further information regarding this company or William Everhart.

undisclosed location was razed and under its foundation is an 1870s trash pit. We’ve pulled several very old bottles from this site and the Everhart blob pictured is no exception. William Everhart started his “bottling house” in Easton, Pa. in 1877. Everhart bottled an assortment of beers, such as lager, porter and ale. He also bottled mineral water and soda. The bottle (above) is a soda that contained about six ounces of liquid- scarcely a mouthful by today’s standards. Everhart’s business was located at 12 North Fifth St in downtown Easton. According to an 1881 write-up in Manufacturing and Mercantile Resources of the Lehigh Valley William Everhart “built up a large trade in Easton and its neighborhood…” In addition according to the review, one of Everhart’s specialties was birch beer which was “highly prized” by the community. Today Everhart bottles sell for around $10. Currently, we have no further information regarding this company or William Everhart.

Embossed on the back of the Everhart soda is this very crude five-pointed star trademark symbol. (Shown right) The stylized letter “E” undoubtedly stands for Everhart.

![]() PEOPLE’S CHEMICAL COMPANY BEEF, WINE AND IRON: RARE -MAYBE- A NICE ADDITION TO ANY ONE’S COLLECTION, CERTAINLY.

PEOPLE’S CHEMICAL COMPANY BEEF, WINE AND IRON: RARE -MAYBE- A NICE ADDITION TO ANY ONE’S COLLECTION, CERTAINLY.

During the 19th and early 20th century, one of the most popular patent medicines was beef, wine and iron. Consequently, local druggist and provincial firms joined the market with their own lines of the well-liked nostrum. One of these firms that came late in the game was People’s Chemical Company out of Providence, Rhode Island. Acts and Resolves of the General Assembly of Rhode Island indicate People’s Chemical Company filed an agreement to form a corporation in January 1907. However, the business may not have incorporated until the 1910s. Regardless, the establishment’s first location was at 559 Westminster St which separates Providences’ Federal Hill district from the cities’ West End. At the time, Federal Hill was heavily populated with Italian immigrants. It’s uncertain if People’s Chemical employed Italians at their facility but it is possible. The firm eventually moved to 83 Sutton St for about two years then relocated to 193 Salina St or Salina Ave depending on sources. The company was the brainchild of three Providence Rhode Island citizens: Enrest E. Melfi, William J. Brown and Charlotte E. Stimets. Although People’s sold a host of tonics, One of the firm’s most popular potions by far was Scientific Improved Beef, Wine and Iron. A hundred years after the beef, wine and iron craze ended today’s diggers are discovering these tonic bottles and one of the first we at Hat City Diggers discovered was People’s Chemical Beef, Wine and Iron. The prevalence of this Rhode Island bottle depends on who you talk to. I spoke with one Rhode Island Digger who said: “I’m pretty sure I’ve never seen this bottle.” Another digger from the Ocean State said that he’s never dug a People’s Chemical but he knows of the bottle, researched the company and doesn’t consider People’s Chemical Beef, Wine and Iron rare. Either way People’s Chemical Company Beef, Wine and Iron is far from your garden variety patent medicine. According to local historian and avid Rhode Island bottle digger and collector Taylor McBurney although People’s Chemical, in his opinion, would be an “‘important'” addition to Rhode Island diggers’ collections because of its “pleasing form and embossing… [Rhode Island] collectors would be happy to acquire one.” Despite the difference in opinion, People’s Chemical was popular enough to make it from Rhode Island to Danbury. However, it’s hard to know how popular the drug was in the city considering a host of companies were selling beef, wine and iron at the time. So far we’ve recovered two of the Rhode Island tonics from Danbury trash pits. Ultimately the dumps we dig may have the final say on the nostrum’s popular in Danbury. Of all the Danbury dumps we’ve dug we’ve only recovered one kind of beef, wine and iron: People’s Chemical Beef, Wine and Iron. However, considering most bottles from the 19th and early 20th century were not embossed this evidence is spurious at best since we may have already recovered dozens of beef, wine and iron bottles and not known it. Finally, by 1918 the firm is no longer listed in Providence city directories. In the end, People’s Chemical appears to have been a victim of bad timing. If the company had started business 20 years earlier, and not during the Progressive Movement of the early 20th century, its beef wine and iron tonic may have become a household name. But because of its late start, the firm was beguiled by new regulations, a scientific community skeptical about the validity of patent medicines and the influence of the temperance movement.

![]() COMMONLY UNCOMMON: P. J. CRAY IN DANBURY, CT.

COMMONLY UNCOMMON: P. J. CRAY IN DANBURY, CT.

We’ve never gone digging in Holyoke, Mass. but it’s very likely P. J. Cray Bottling Company sodas like the one pictured are very frequent find for diggers from that area. In Danbury, however, the bottles are unusually rare. In fact, this is the only example we have ever found. Nevertheless, it stands as proof P. J. Cray was distributing soda throughout New England at the turn of the century. Today Cray is forgotten but during his time he must have been quite the businessman, that is to say, he was popular enough to win a write-up in Holyoke: Past and Present, Progress and Prosperity… Souvenir 1910. According to the- Souvenir– P. J. emigrated from Ireland. His vocations varied. For a time, he was involved in the “granite business in Quincy, Mass” and at one point he lived in Scranton, Pa. Eventually, though, P. J. found his way to Holyoke and in 1902 started the P. J. Cray Bottling Company at 676 East St. Cray’s firm bottled an assortment of beverages including the companies’ celebrated Cataract ginger ale, “soda water and various tonics.” The business continued after P. J.’s death well into the twentieth century. The Cray bottle shown was blown in a mold and held about six to eight ounces of soda. It dates to the turn of the century and is likely an early example.

![]() THE FORGOTTEN GIANT: AMERICAN SODA FOUNTAIN COMPANY.

THE FORGOTTEN GIANT: AMERICAN SODA FOUNTAIN COMPANY.

During the golden age of the drugstore soda fountain, there was no name bigger than American Soda Fountain Company. With branches stretching the globe the sun truly never set on the firm’s empire. Today hardly anyone remembers this giant in the industry. But a hundred plus years ago the corporation was renowned in the soda fountain apparatus business with their fountains being some of the most sought after in the world. According to The Soda Fountain by Gia Giasullo and Peter Freeman the enterprise had its beginnings with four companies which dominated the “supply of wall fountains and fountain appliances.” Four men ran these firms: John Matthews of New York, James W. Tufts and A. D. Puffers of Boston and Charles Lippincott of Philadelphia. In 1891 A. D. Puffer and Sons, the Charles Lippincott Company, John Matthews and James W. Tufts joined forces and formed what became the largest soda fountain manufacturer in the world. At its height, American Soda Fountain Company had branches across the U.S. and the globe. The company was located in Boston, Mass, New York, N.Y., Dallas TX., Philadelphia Pa., Chicago, Ill., Atlanta, Ga., Denver, Col., San Francisco, Ca., Johannesburg, South Africa, London, England and Melbourne, Australia. It stands to reason the creation of such an immense corporation made its four capitalists: Puffer, Lippincott, Matthews and Tufts very wealthy men, however, if anyone one of them were considered a central figure of the firm it would have to be James Tufts who in his youth had pioneered the development of soda fountains. Sources indicate James was born in Charlestown Mass. in 1835. “At age [15] he became an apprentice [for druggist] Samuel Kidder… in Charlestown.” By the age of 21, James opened his own pharmacy. According to Dictionary of North Carolina Biography edited by William Powell, James opened at least three more pharmacies in Massachusetts. From another source Bulletin of Pharmacy for January 1902 we learn that while at his firm in Medford, Mass he conceived a soda water apparatus that he eventually patented. Soon Tufts was selling more apparatus than his competitors. James used marble and silver plating on his “elaborately constructed fountains” which he branded: Arctic Soda Apparatus. Naturally, when Tufts and the others formed the American Soda Fountain Company it was James Tufts who emerge as its leader and first president. James Tufts remand the firm’s president until his death. He died of heart failure on February 2, 1902. The firm continued without him under the leadership of James N. North who had studied theology at the Harvard Divinity School. After 1914, records become scant about the corporation. We do know changes occurred at the firm around this time. The New Jersey branch of the firm closed and in 1915 Isaac F. North was elected president of the Maine branch. Whether Isaac controlled the entire corporation is not clear. Before I close there are several points of interest I’d like to note. The average price of an American Soda Fountain Company apparatus was $1000. One of their most expensive fountains was built for the William B. Riker and Son Company of New York. The apparatus cost Riker $20,000 was 36ft long, made of fine marble and onyx and had solid brass bases and bronze capitals The bottle above comes from a dump we dug last summer in Danbury, Ct. In all likelihood, it dates to about the time James Tufts died and contained tonic water. We consider this bottle a rare find, at least to Danbury area dumps.

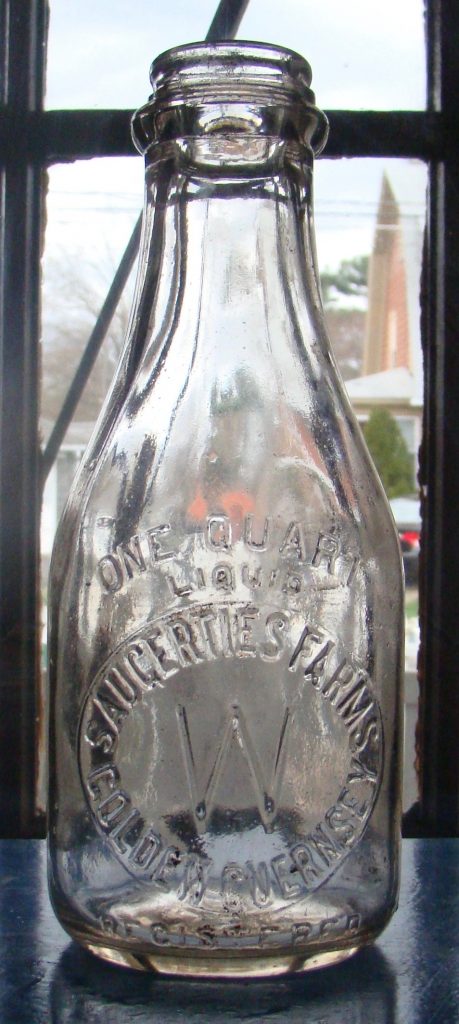

![]() FROM THE MOST EXPENSIVE COWS IN THE HUDSON VALLEY: GOLDEN GUERNSEY MILK.

FROM THE MOST EXPENSIVE COWS IN THE HUDSON VALLEY: GOLDEN GUERNSEY MILK.

Research indicates James O. Winston was one of Saugerties N.Y. most wealthy men. And records suggest he bred some of the most expensive cattle in the state. The cattle weren’t Winston’s only valuable assets. According to the 1919 Guernsey Breeders’ Journal Winton’s farm was a massive 800 acres 200 of which was “under cultivation.” The farm consisted of some of the finest farm animals money could buy not only were there 23 first-rate purebred milk cows but there were also an unspecified amount of thoroughbred horses, “[a] flock of twelve hundred White Leghorn hens”, forty purebred Hampshire Sheep and thirty Berkshire pigs. Of the livestock, however, the cattle were the most prized. Guernsey Breeders Journal for January 1922 states two of James’ Guernsey cows sold for boo koo bucks and from The Field Illustrated for January 1922 we learn Winston sold a prize bull, Ultra May King for $6000. Incredibly that’s over $87,000 in 2017 money. Winston was so proud of his Guernsey stock he let everybody know his milk was golden Guernsey milk (see bottle). In later years ownership of the farm changed hands several times. In the 1970s a landfill was proposed at the farm site. The people of Saugerties successfully fought against this plan. In 1994 The farm made national news when the site hosted the massive Woodstock 94 concert. We were fortunate enough to attend this epic festival where bands such as Green Day, Aerosmith and Blind Melon performed. In any event in 2016, the historic farm was threatened with development with proposals for a hotel or casino. At this time no development has yet occurred. We dug the Saugerties Farms milk (above) from an ash layer we discovered on a recon trip Saturday, April 15, 2017, to Saugerties N.Y.

![]() GEO. KLETT AND KUTSCHER BROS’: TWO HEARTBREAKERS FROM THE TRI-STATE.

GEO. KLETT AND KUTSCHER BROS’: TWO HEARTBREAKERS FROM THE TRI-STATE.

Sometimes you find bottles that you just wish you never discovered- only because of how terrible they make you feel when they come out of the ground mangled, cracked or just falling to pieces. The two beers above fit agonizingly well in this dreaded category. Though not scarce, both still would have made fine additions to our collections. However, alas, now they are now destined for the junk heap- but not before I impart to you a bit of information about each bottler. Next to nothing is known about George Klett and his enterprise. Trow’s Business Directory of Manhattan and The Bronx provides us with the same information as the Klett bottle itself: Klett bottled beer in the Bronx neighborhood of Nan Nest and his firm was located on Columbus Ave near Jefferson St. The last snippet of information about Klett comes to us from The American Bottler magazine for January 1907. According to The Bottler, Klett was expelled from the Bottlers’ and Manufacturers’ Association of New York. Disconcerting news, yes, however, no reason for the expulsion is given. Beyond that revelation, we know nothing else. Information on the Kutscher Brothers’ operation is more forthcoming. According to The Commemorative Biographical Record of Fairfield County, the driving force for years of Kutscher beer was Louis Kutscher Sr who emigrated from Germany to America as a young man with his family, however, by 1891 Louis had retired and was no longer associated with the firm. Louis’ sons, Louis Jr and William took possession of the enterprise. The Commemorative Biographical Record of Fairfield County for 1899 shares these details about Louis Jr with us. Louis was born in New York City in 1868. “[D]uring his infancy his parents removed to Bridgeport.” When Louis was 21 he entered business with his father. Finally, after Louis Sr stopped working, the brothers managed the firm under the name Kutscher Brothers for four years then for reasons unknown the brothers terminated their partnership in 1896 and the company was, “dissolved.” The beer (right) is a Weiss beer by the firm Kutscher Brothers and dates between 1892-1896. The Geo. Klett (left) dates to about 1900.

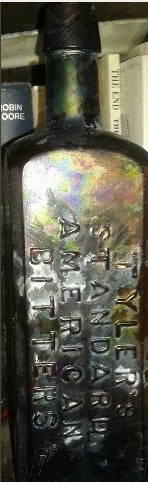

![]() HOT TUNA.

HOT TUNA.

RARE DEPENDING ON CONDITION VALUE $900+

Very little is known about this extremely rare bitters out of Connecticut. What we do know about Tyler’s Standard American Bitters comes from an 1870s ad circulating around the internet. The firm was located at 171 State St New Haven, Ct. J. Tyler Jr (was most likely the bitters’ namesake), H.P. Frost and T.S. Foote ran the firm. Beyond this pocket-sized information, nothing else is known. We dug the bottle pictured above from a dump located in New Milford, Ct in 2015. That same year we sold the Tyler’s at auction for over $900. The bottle became somewhat of a minor celebrity when it was featured on the website Peachridge Glass.

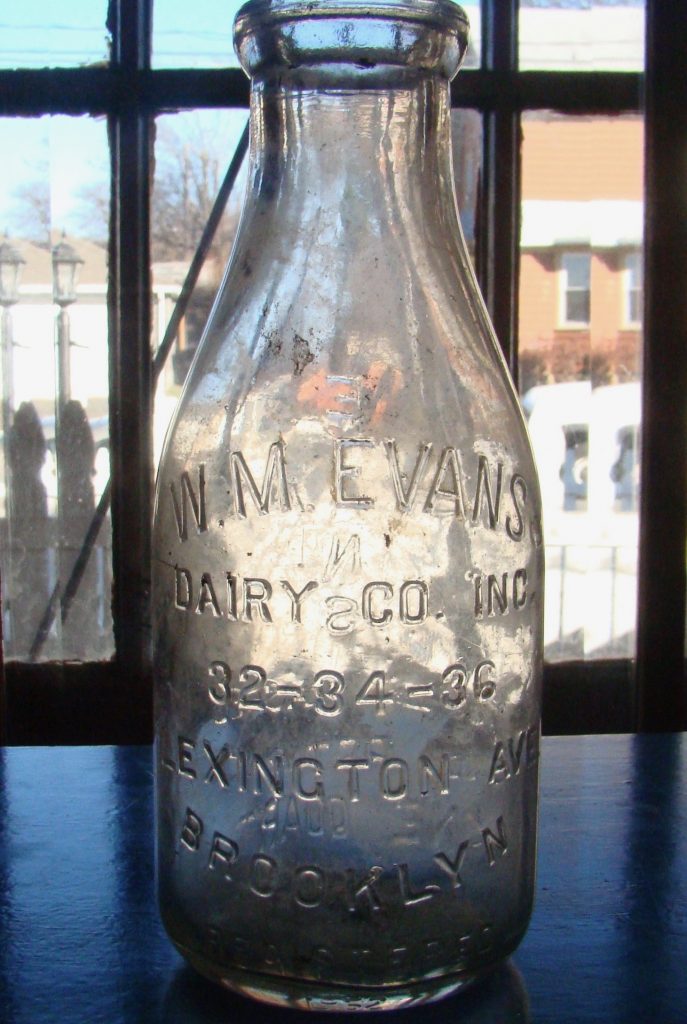

![]() Taken from a cellar hole, in the eerie Joe’s Hill area of Danbury and New York State, a milk: W. M. Evan’s Dairy Co. Inc.

Taken from a cellar hole, in the eerie Joe’s Hill area of Danbury and New York State, a milk: W. M. Evan’s Dairy Co. Inc.

Joe’s Hill Rd courses through a remote area on the Danbury, New York State border. Gnarled trees line the narrow neglected road of holes and soft patched asphalt lumps. To the right of the lane is Farrington’s pond its waters motionless and black. Legend has it the Leather Man spent time in this area on his long circular journey through Connecticut and New York. Adding to the district’s creepy mystique is the 1989 thrill killing of a college student by two misfit teenagers, the lore of the Jesus Tree, and the massive Morefar estate just across the border in the town of Southeast, N. Y. Near this border is where you find the “Joe’s Hill” bottle dump, tucked away in an 18th-century cellar hole among poison ivy, sugar maples, ashes and oaks. Normally we’d keep a site like this on the down-low but we dug it out several years ago and there is nothing of value left. During the dig we uncovered a number of milks most were junk, however, the Evans (above) with its heavy embossing was an exception. W. M. Evans, a mainstay in Brooklyn’s Williamsburg neighborhood, was an independent milk dealer for years. First located inland the dairy eventually moved to a site along the East River then to its final location at 32-34-36 Lexington Ave, near Bedford Stuyvesant. What we learned about the company comes mostly from Lain’s and Upington’s Brooklyn City Directories and the Interlaken Review of Seneca, N.Y. Willet M. Evans found the dairy in 1878. In 1904 Willet’s son, William, bought the business, “and launched out on his own hook with seven wagons and ten horses.” The company grew: operating at its height 226 routes. In 1913 William Evans incorporated the firm. For over 40 years W. M. Evan’s Dairy was an independent operation than in 1925 the Dairymen’s League Co-operative Association, according to the Interlaken Review, “purchased the business and properties.”

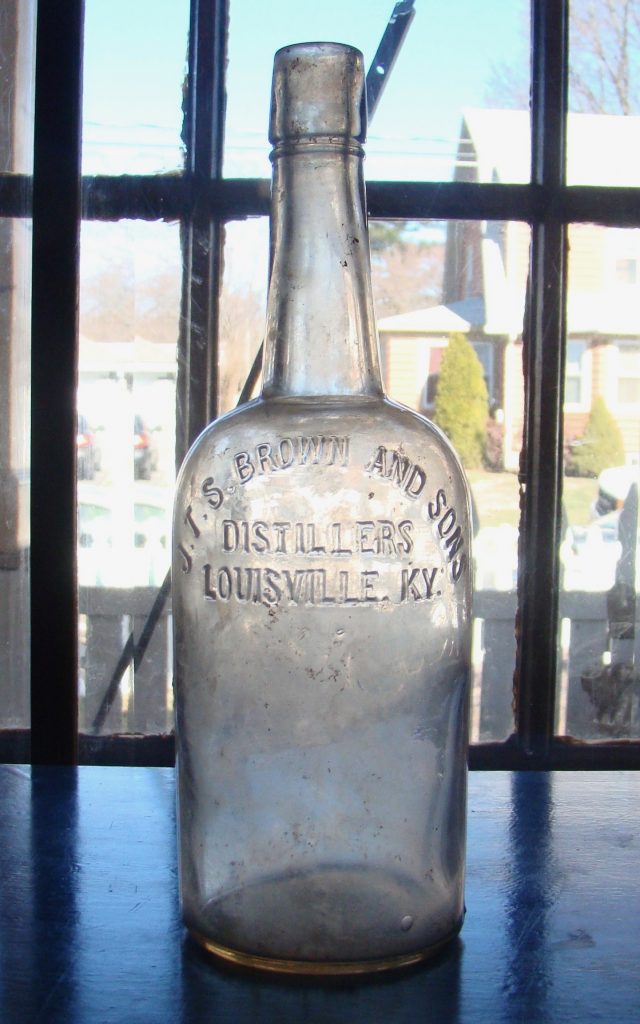

![]() THE CLASSIC: J.T.S. BROWN.

THE CLASSIC: J.T.S. BROWN.

J.T.S. Brown is forever fixed in popular culture when it is famously requested by Paul Newman, as, “Fast Eddie” Felson, in Robert Rossen’s 1961 classic film about pool sharks, The Hustler. Beyond Tinseltown, the firm itself has a rich and complex history, and now, well over 120 years old, still continues business selling whiskey. John Thomas Street Brown started the company with his partner Joseph D. Allen in the 1850s. When Allen retired, the business incurred a name change. After the Civil War, Brown’s sons came aboard and the companies’ name was changed again this time to J.T.S. Brown and Sons. The bottle (above) dates from this period. To learn more about the Brown family and it company visit. Pre-prowhiskeymen!. The site is well researched and worth a visit. We end with a short passage from Walter Tevis’ 1959 novel, The Hustler:

“Eddie grinned, liking the feeling of this, the getting ready for action. He fished out a ten himself. ‘J.T.S. Brown bourbon,’ he said to the thin man. Then he leaned his cue stick against the table, unbuttoned his cuffs, and began rolling up his shirt sleeves. Then he stretched out his arms, flexing the muscles, enjoying the good sense of their steadiness, their control, and he said, ‘ Okay, Fats. Your break.’ Eddie beat him.”

![]() MEXICAN MUSTANG LINIMENT: AN OLD WEST ICON.

MEXICAN MUSTANG LINIMENT: AN OLD WEST ICON.

Today the name Mexican Mustang Liniment invokes images of the old west. The bottles can be found at mining camp, forts, and other archeological sites throughout the west from Arizona to California, Colorado to Texas. However, millions of the bottles, which varied in size, were sold across the entire U.S. in the 19th century. Lyon Manufacturing Company of New York, the agents of the cure-all, claimed at least 300 livery stables in New York City alone were, “using the Mexican Mustang Liniment.” on their horses. People sent testimonials from everywhere professing the liniment’s powers. The nostrum was very popular with the poultry community who claimed the liniment cured roup in their chickens and ducks. Nevertheless, the mountains of liniment appear not to have made it to Danbury. Mustang Liniment bottles are extremely rare finds in local dumps. In our years of digging, we’ve only recovered one of the liniment bottles. On the contrary, Bromo Seltzer, another big seller is found everywhere in the Danbury area. In any event, the history of Mustang liniment is a little sketchy. The nostrum predates the Civil War. According to the Lyon Company, the liniment originated after the Mexican American War, in fact, some of the cruder pontiled variants from this era can be quite desirable. The bottle above dates to the turn of the century.

![]() FROM A GIANT NEW ENGLAND ASH DUMP COMES A GIANT OF A FIND: BASTINE & CO PURE FLAVORING EXTRACTS.

FROM A GIANT NEW ENGLAND ASH DUMP COMES A GIANT OF A FIND: BASTINE & CO PURE FLAVORING EXTRACTS.

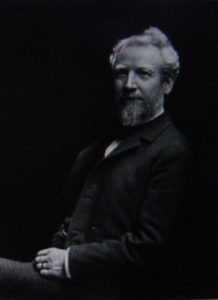

Without revealing its location, I can say the ash dump behind a large Queen Ann style Victorian home was one of the biggest we ever dug. From the top of the embankment to the bottom of the woodlot, this dump is at least 15 feet high. Given this, a collapse of ash could bury you in seconds. Nevertheless excavating an ash heap this size was well worth the risk. Because hidden deep within the fine ash were hundreds of discarded Victorian and Edwardian era bottles. Most of them were junk, but we did find a few keepers, such as the mammoth (it’s well over a foot tall) Bastine & Co Pure Flavoring Extract, above. Considering how high the embankment is it’s a wonder this biggin didn’t get smashed to pieces when it was discarded. Very little is known about Bastine and Company: The owner of the firm was Andrew J. Bastine sources tell us he lived in New Rochelle N.Y. and the location of his company was lower Manhattan at number 19 Warren St in what is now called Tribeca.

Andrew Bastine seated for a photograph in a 1902 publication: New York, The Metropolis.

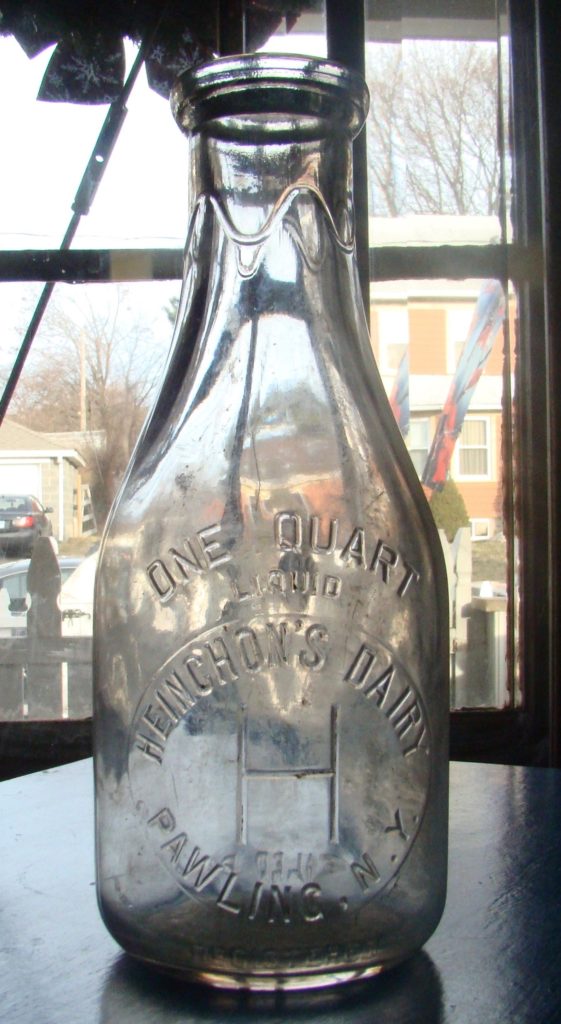

![]() FROM HUMBLE A BEGINNING TO A PAWLING LANDMARK- HEINCHON’S DAIRY.

FROM HUMBLE A BEGINNING TO A PAWLING LANDMARK- HEINCHON’S DAIRY.

In the beginning, Danial Heinchon’s dairy operation was so small he made deliveries by foot and the milk was kept cool in a stream on the property. Eventually, Heinchon’s Dairy became one of the biggest enterprises in Pawling with deliveries being made as far as New York City. According to the Poughkeepsie Journal, at its height, the dairy had over 100 cows. Danial, a native of Pawling, was born in 1896. He served in the military and was a WWI veteran. A few years after the Great War Danial established his firm. For years the dairy was a landmark on Rt 22 in Pawling and business was brisk. In 1965 the dairy had a setback when the Heinchon’s large dairy barn was set on fire. the animals were rescued but the barn was a total loss. Luckily the arsonist was caught. A few miles away the Heinchon’s built a new barn. But the fire that could have ended in disaster was not far from their minds. “[But] from the ashes of that day,” according to Connie Johnson Hambley, writing for Pawling Public Radio, “rose an inner resilience and strength to carry on.” Setbacks weren’t going to bring the family down the Heinchon’s had roots in Pawling and at their core was the families dairy business but they had another foundation- ice cream. The Heinchon’s ice cream was some of the most popular- drawing people from near and far since 1923. According to Alice Gabriel of the New York Times “Big sellers are Hudson Harvest (vanilla ice cream churned with local raspberries, whole almonds and chocolate chips), Mud pie (coffee ice cream with fudge ripple and Oreo cookies) and smooth black raspberry.” Sadly in 2016 the ice cream parlor, a yellow one-story house on Rt 22, closed and has not reopened. The Heinchon name has also been removed from the building. In 1978 Danial Heinchon died and a close relative Kent Johnson took over the operation. In time the Heinchon’s diversified and the company appears to be no longer in the milk business. The bottle (above), a Heinchon’s Dairy from the 1930s, is one of two discovered during a dig in Pawling two years ago.

The friendly reminder to, “return bottles daily” didn’t keep the user of this Heinchon bottle, ca 1930s, from tossing it down an embankment years ago.

![]() FROM STAMFORD, CT COMES A RARE FIND FROM THE SHORT-LIVED ACME BOTTLING WORKS.

FROM STAMFORD, CT COMES A RARE FIND FROM THE SHORT-LIVED ACME BOTTLING WORKS.

Wilbur E. Lewis’ Acme Bottling Works was here today gone tomorrow, needless to say, the brevity at which the business ceased trade doesn’t seem to have impacted the dearth of the firm’s bottles- Hat City Diggers has found two in Danbury so far. Sources indicate Wilbur E. Lewis, was born in 1856 and came to Stamford in his, “boyhood.” Wilbur tried his hand in the drug trade before establishing his bottling works. In 1880 he opened a drug store “in the northeast corner of the old Town Hall. ” Eventually he moved the business to Atlantic St and ten years later he sold the firm to Mr. J. D. Goulden. About 1890, Wilbur established the Acme Bottling Works at 14 State St. According Trows City Directories, the company was “dissolved” that same year. If accurate, this would mean Acme was only open a few months. Why Wilbur closed the firm is not known. After bottling, Wilbur became a successful salesman. He died, according to news reports, from the grip and an ear infection in May of 1921. The Acme Bottling works soda (above) comes from a dump in Danbury. We found another of the slender blue bottles creek walking in the spring of 2017.

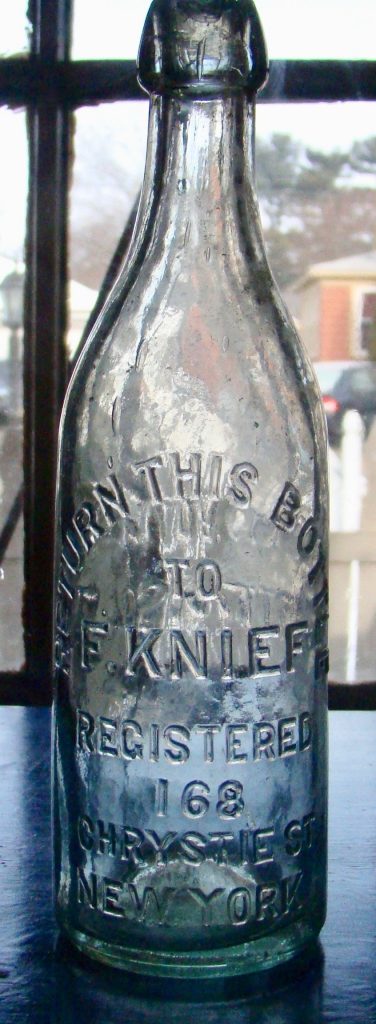

![]() FROM THE BELLY OF THE BEAST- FRANK KNIEF BEER.

FROM THE BELLY OF THE BEAST- FRANK KNIEF BEER.

Even with a name like Knief, we can’t attest to Frank Knief’s character but if the location of his saloon is any indication of Frank’s nature he must have been a rough and tumble sort of guy. According to Trow’s New York City Directory Frank Knief started bottling beer on Chrystie St in the heart of Manhattan’s Bowery about 1889. By the 1890s, The Bowery, a densely populated slum in New York City was home to prostitution, dance halls, flophouses and saloons that catered to the cities’ homosexuals. Frank Knief moved his business at least two times during the 1890s, first to 14 Rivington St, not far from the cities’ Little Italy, then to 140 east 12th St. Knief may have relocated because of the Bowery’s”bawdy” environment but likely cheap rents were the real incentive. About the time of the moves, Trow’s lists Knief as a “water” dealer. With such a vague description there’s no way of telling whether Knief was bottling soda or mineral water. The last entry for Knief in the directories is 1905. We dug this heavily whittled bottle (above) from a dump in New Milford, Ct- a far cry from New York’s skid row.

![]() THREE ENIGMAS FROM THE NUTMEG STATE.

THREE ENIGMAS FROM THE NUTMEG STATE.

Digging up information on the beers pictured was a lot more difficult than unearthing the bottles themselves- and less rewarding! Here’s what little we know: The W. T. Gray (left) comes from South Norwalk the enterprise was located on Strawberry Hill in that part of town. The Eagle Brewing Co Inc (center) out of Waterbury, Ct is a really nice piece with its oval slug plate and cascading words but nothing is known about the enterprise other than the firm bottled the standard fair of beer, ale and porter. The Connecticut Breweries Co (right) out of Bridgeport was a true brewery in every sense of the word. The firm brewed its own beer on-premises. In 1916 the company planned to upgrade its facility by adding a “new ice plant” and, “[a] new one- story and basement structure to be equipped for a stock and fermenting cellar…” These three enigmas all came from dumps located in Danbury.

![]() Joseph Deni beer. Discovered a few years ago-painfully little is known about this bottler.

Joseph Deni beer. Discovered a few years ago-painfully little is known about this bottler.

The information on Joseph Deni we gathered, painfully little at that, comes from sources we found on the internet. Here is what we gathered: Joseph Deni bottled beer and liquor at 1308 (some sources indicate 1306) Unity St in Frankford, a small borough in northeast Philly. We believe Deni was of Italian descent. (Joseph vouched for at least two Italians petitioning for naturalization in the late 1910s). Besides liquor, we found evidence Joe may have run a small bakery in Frankford. Joe appears to have been active in the liquor trade up to prohibition. The blob top (above) dates to the early 1900s.

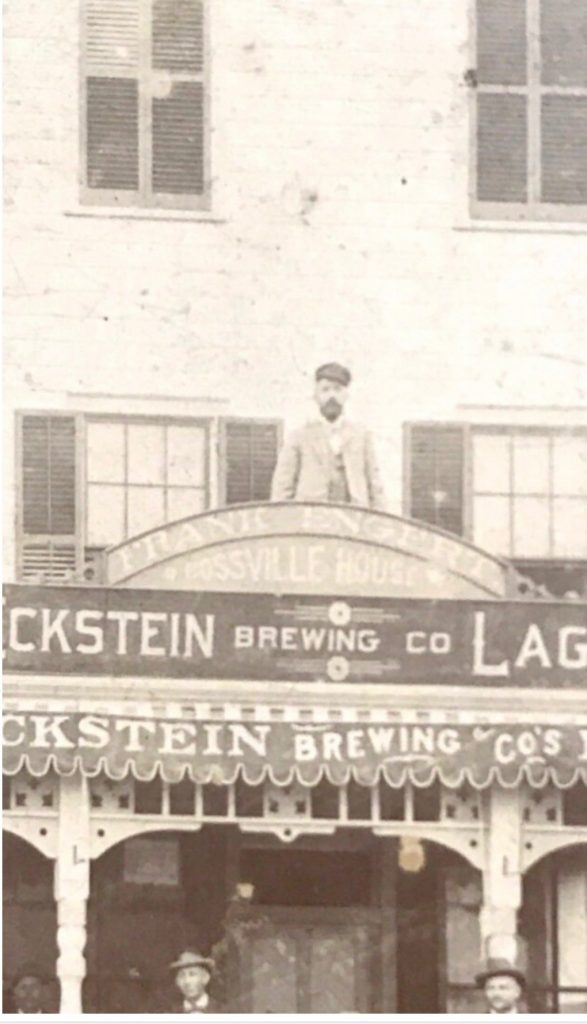

![]() FRANK ENGERT- A BOTTLE FOUND, A LIFE REVEALED.

FRANK ENGERT- A BOTTLE FOUND, A LIFE REVEALED.

When Frank Engert died in a freak accident he left behind not only a family but a hotel enterprise together with a coal trade, grocery and stage business. But as the bottle above demonstrates Frank was also bottling beer. And if not for the unmistakable reality of this bottle Frank Engert would have remained forgotten 100 years after his death.

LIFE AND DEATH ON THE ISLAND

Frank spent most of his life on Staten Island. For at least thirty years he resided in the town of Rossville on the island’s south shore. Frank was known as the Mayor of Rossville but this can not be confirmed. However, for 22 years Frank ran the Central Hotel in Rossville on Fresh Kills Rd. With all certainty, Frank sold his beer at the Central Hotel and throughout the Tri-State area. We dug the bottle pictured from a dump in Danbury over ninety miles from Rossville. The cross on the bottle may hold some significance, however as yet we are unable to determine the variant. It looks similar to the German iron cross and Engert is a German surname. However, beyond these details, we know nothing else about the puzzling graphic. Ironically in 1912, Frank’s life was cut short when he was injured severally from a fall into a coal barge. The New York Tribune for 1912 writes that [Frank was supervising] “…the unloading of coal from a barge at his dock when he was caught by a guy rope and was jerked into the air and then dropped into the hole of the barge…” He sustained head and internal injuries and died a week later at his home. He was 52 years old. Frank left behind a wife, four sons and five daughters. The Frank Engert (above) dates to the 1900s. Finally if not for the discovery of the beer (above) the life of Frank Engert would have been forgotten. Ultimately it’s not his huge family, the Central Hotel, the coal, stage or grocery business but a discarded beer bottle from a second- rate bottling business ( his obituary completely overlooked the firm) that cements Engert’s legacy. And this suits us just fine here at Hat City Diggers.

The Rossville House hotel (date unknown). Frank is standing on the roof overlooking the street. (photo courtesy the Walsh family)

![]() From the demolition site an early soda or mineral water- Henry Menken New York.

From the demolition site an early soda or mineral water- Henry Menken New York.

Information is scarce on Henry Menken. What we do know comes from the New York City Directories 1864 – 1873. Menken’s bottling works was located at 31 9th Ave and later 405 west 13th St. Menken didn’t move far when he changed addresses. Both locations are on Manhattan’s west side and walking distances from each other. In 1873 Menken appears to have been bottling beer as well as soda. By 1887 Henry may have died. He is no longer listed as running the firm. John H. Menken, possibly Henry’s son, replace him as proprietor. We dug the bottle pictured from a construction site in downtown Danbury. Like most bottles from this site, the Menken bottle is damaged.

Information is scarce on Henry Menken. What we do know comes from the New York City Directories 1864 – 1873. Menken’s bottling works was located at 31 9th Ave and later 405 west 13th St. Menken didn’t move far when he changed addresses. Both locations are on Manhattan’s west side and walking distances from each other. In 1873 Menken appears to have been bottling beer as well as soda. By 1887 Henry may have died. He is no longer listed as running the firm. John H. Menken, possibly Henry’s son, replace him as proprietor. We dug the bottle pictured from a construction site in downtown Danbury. Like most bottles from this site, the Menken bottle is damaged.

The reverse of the Menken (right). Note the large capital letters common on bottles of that era.

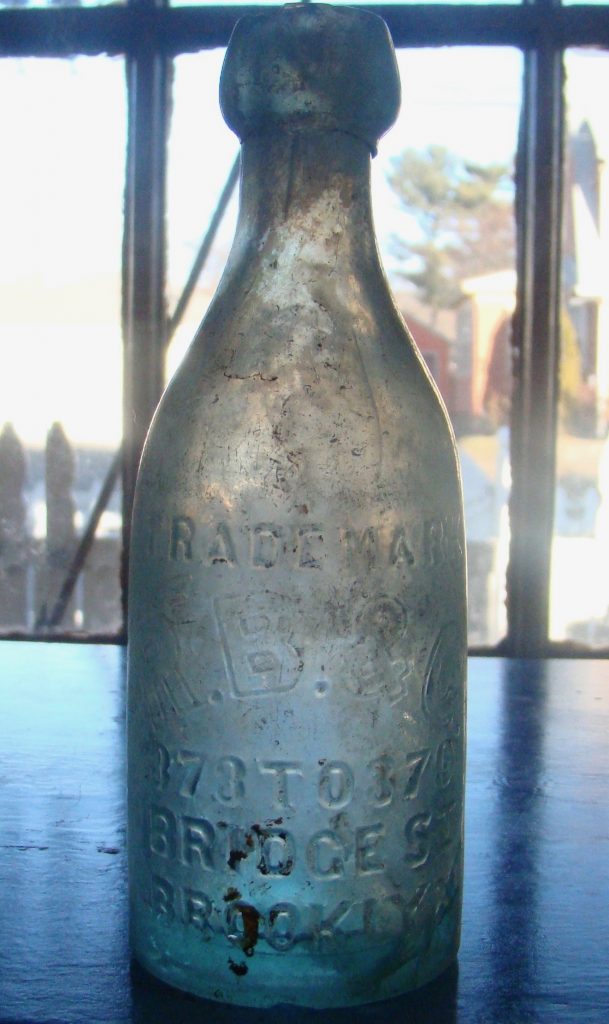

![]() ANOTHER DEMOLITION SITE FIND.

ANOTHER DEMOLITION SITE FIND.

The 1871 Brooklyn Directory list Russell Brothers and Goodwin Mineral Water at 325 Pearl St, Brooklyn. This bottle, however, clearly shows that by 1873 the firm had expanded to 373- 379 Bridge St Brooklyn. Robert and George Russell and their partner Hugh Goodwin ran the enterprise. In 1880 the Russell Brothers are listed as living together at 369 Pearl St. George was also a supervisor in the 4th Ward. Eventually, Hugh Goodwin began his own mineral water business branching out to Coney Island. He died in 1905 at 69. We dug this bottle on February 6 in the early morning. The bottle has some damage but- all in all- is still a great find.

The back of Russell Bro & Goodwin (right) with the firm’s address clearly embossed. Note the distinctly applied lip (upper right).

![]() FROM BOOM TO BUST: HOW A MAGAZINE RUN BY A MAN WHO STUDIED TO BE A PRIEST AND A MUCKRAKING JOURNALIST BROUGHT DOWN THE GREAT DOCTOR KILMER’S SWAMP ROOT

FROM BOOM TO BUST: HOW A MAGAZINE RUN BY A MAN WHO STUDIED TO BE A PRIEST AND A MUCKRAKING JOURNALIST BROUGHT DOWN THE GREAT DOCTOR KILMER’S SWAMP ROOT

Like Warner’s Safe Cure, Dr Kilmer’s Swamp Root rose to stardom in the late 19th century. S. Andral Kilmer of Binghampton, N. Y. Marketed Swamp-Root starting in 1879. Eventually, Jonas and Willis Kilmer, father and son respectively took over the firm. Swamp-Root, extremely popular, made both men very rich and very powerful in Binghampton. Their fortune was, “estimated at… 10 to 15 million [dollars].” The Kilmer’s virtually owned Binghampton they were immersed in the cities affairs and had considerable influence. Jonas Kilmer was president of the People’s Bank, Willis was vice-president. They owned the cities newspaper, “Jonas Kilmer [had] been… the cities police commissioner… [and] Willis… had congressional aspirations.” Robert Manning in his article The Happy Accident paints a less than rosy picture of Willis Kilmer. Manning relates to the readers an incident between Willis and a bicyclist. It seems Willis could become incensed at the slightest provocation. “One day Willis… driving his tandem through the busy street, became incensed at a bicyclist who failed to give way when he shouted, so he horsewhipped the man.” It was learned later that the man was, “stone” deaf. Although the Kilmers were very powerful, that didn’t stop muckraking journalist Samuel Hopkins Adams from attacking the two in his scathing exposé on Dr. Kilmer’s Swamp-Root for Collier’s magazine in 1912. Adams didn’t mince words when he accused the Kilmer’s and their nostrum of literally defrauding and putting the public in danger. In his story, Adams claimed there was nothing proprietary about Swamp-Root. “Essentially it is alcohol, sugar, water and flavoring matter,” he wrote, “with a slight laxative principle… Field Herbs and Healing Balsams.” Then Adams lists the lies associated with the nostrum i.e. the illnesses the nostrum claimed it could cure. The patent medicine industry had been under the microscope since Colliers exposé six years earlier. That story had facilitated the Pure Food and Drug Act. Now Colliers, with the help of Samuel Hopkins Adams was attacking one of the industries’ giants. Eventually, patent medicines fell out of favor with the public and Willis Kilmer moved on to other ventures. When Willis died in 1940 F. D. R. sent the Kilmer family his condolences. Three Swamp-Roots are pictured. The small bottle (right) is a sample bottle sent to the consumer for free through the mail. As of 2017, Swamp-Root was for sale at Amazon.com but as of late is currently unavailable.

![]() DANIEL CURLEY- SAUGERTIES’ WORKAHOLIC.

DANIEL CURLEY- SAUGERTIES’ WORKAHOLIC.

Danial Curley didn’t bottle just beer in Saugerties N.Y. Curley was a workaholic who wore many hats in the small village along the Hudson River. Not only was he a grocer, liquor dealer and village director but he also moonlighted as the village’s coroner. Which occupation Curley preferred is not known. Despite Danial’s deep roots in the Saugerties’ community, he was not native to the town. Danial “was born in Delhi, a small village 70 miles west of Saugerties. Little else is known about this Mid-Hudson bottler other than he had a son Peter and a grandson Danial who served in France during W.W.I. We discovered this Danial Curley blob at a construction site in Danbury on February 5, 2017. It may date to the 1880s.

![]() WARNER’S SAFE- A PATENT MEDICINE ICON.

WARNER’S SAFE- A PATENT MEDICINE ICON.

The word icon is thrown around loosely today but if there ever was a patent medicine that fit this description it’d have to be Warner’s Safe Cure. During its height, Warner’s could be found in all corners of the world from England to Australia. The inventor of this celebrated nostrum was Mr. H. H. Warner. At his apex, Warner was a millionaire many time over. Warner’s start in the world was quite humble, however. Contemporaneous reports have Warner born on a farm. At 15 Warner moved to Memphis to apprentice as a “tin-smith.” Warner’s odyssey continued when he moved to Michigan. While in the Wolverine state, Mr. Warner procured a hardware store. “This business failed after a run of five years.” Continuing his journey to fame and fortune, H.H. Warner began a career as a traveling salesman selling of all things, safes. Business was good and eventually, Warner opened his own safe manufacturing business in Rochester, N.Y. In the meantime, Warner found time to marry- twice. All work and no play made Mr. Warner a very sick boy. He developed kidney disease. His doctor prescribed a mysterious concoction and lo and behold Warner was cured. Warner- ever the businessman- convinced the good doctor to go into business with him. “The words ‘”safe cure”‘ were invented by Mr. Warner as a kind of pun upon his business in iron safes.” Business boomed as Warner’s Safe Cure rocketed to stardom. An 1888 ad for Warner’s claimed to have cured everything under the sun: “Lame back, cured!” “malaria, cured!” “rheumatism,” you guessed it, “cured!” By God, it even claimed to cure a “woman’s friend!” By 1885 Warner’s firm claimed to have sold over 20 million bottles of the nostrum. In addition to his famous Safe Cure, Warner developed a diabetes cure that is prized by collectors today. Mr. Warner’s medicines made him a very, very rich man. The rest is history- well, sort of. You see H.H. Warner (incidentally his name was Hulbert Harrington Warner) lost a lot of money, in fact pretty much all of it. Warner spent lavishly- especially on advertising-$ 5,000,000 by one account. In addition, Warner built an astronomical observatory for a $100,000, procured a seven-story building for the safe cure business, constructed a $150,000 home for himself and bought a “splendid yacht.” Warner also invested heavily on Wall Street with dire consequences. “[T]he notorious Stock Exchange operations between [Warner’s company] and a party of professional stock-wreckers… ended in the complete rout of [Warner].” After the Wall Street fiasco, Warner had to declare bankruptcy. Besides Wall Street, Warner had troubles closer to home. Warner, a pugnacious man, quarreled with the leaders of his church. Warner finally left the church. He was an Episcopal. Warner also had “chronic” issues with the Baptists. When they had the “temerity” to build their church next to his prized observatory, H. H. threatened to tear down the Baptists’ church and build an Episcopalian one in its place. Mr. Warner also immersed himself in the municipal affairs of Rochester and, “when things were conducted in a way that did not suit him…” he bullied the city with blackmail threatening to take his business elsewhere. The bullying notwithstanding, it should be noted that Warner involved himself in quite a few philanthropic ventures in his life. After bankruptcy, Warner tried to rebuild his empire with another patent medicine scheme. But he never again acquired the same fame. He died in 1923. The bottles (above) date to the 1880s or 90s. We dug the one (left) out of a riverbank in New Milford. The other bottle was dug up in Danbury.

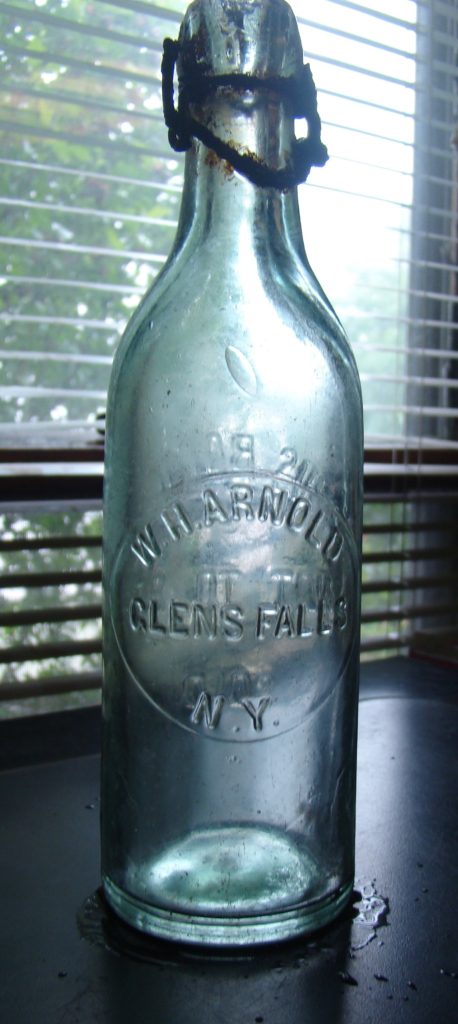

![]() THE STORY OF WILLIAM H. ARNOLD IS ONE WITHOUT AN ENDING.

THE STORY OF WILLIAM H. ARNOLD IS ONE WITHOUT AN ENDING.

Source material starts strong on William H. Arnold then peters out. This is what we know: Before 1889 Arnold was a horrendous businessman he had incurred “judgments” against him between $40,000 and $50,000. That’s over a million dollars in today’s money. Then William moved to Glen Falls, N. Y. a town located along the Hudson River not far from Lake George. With the help of his mother, Maria Arnold, William became quite successful. [ W. H.] “made a verbal agreement with his mother by which he was to conduct business in her name.” We’re not sure if Maria was wealthy but she did own real estate in Amsterdam, N. Y. about 46 miles from Glen Falls. William was her only child. In no time, William opened a liquor firm. He bought goods and wagons and opened an account at the Glen Falls bank. Oddly there was [no] “sign at his place of business.” Four years later William expanded the business, “[A]dding the bottling of soda and other drinks.” In 1897 Maria died. She left her estate in the hands of a trusty. William’s business continued to flourish after his mother’s death and, at one point, he added two more buildings (one would burn). The sources then indicate in 1903 William had trouble with the courts, the problem seemed to stem from the disposition of money. He was held in contempt and fined $261.11. William, who prior to 1889, had been in debt for some $50,000 appealed. Records report William H Arnold died in 1917. Finally, research indicates William’s mother appears to have been the guiding force in his life and when she died, William, who was obviously bad with money, had gotten himself into more trouble. It would be quite interesting to know what became of him. We believe the W.H. Arnold (above) dates to the 1890s or early 1900s.

![]() Dire Straits: the history of Pickman Brothers and Slawson & Decker Co in Pawling.

Dire Straits: the history of Pickman Brothers and Slawson & Decker Co in Pawling.